70

Kids are highly inappropriate. And rude. That’s why they don’t get invited to parties. Kids think it’s appropriate to ask anybody their age. [Cue squeaky voice: how old are you?] They are always asking about your age. Maybe that’s how they calibrate life. Maybe that’s their ice-breaker. Maybe if they know how old you are they can filter what to tell you and what not to tell you. Because adults can also get sensitive. And pitious.

My son, Kim, is greatly fascinated by the fact that I was born in 1977. He keeps asking me which year I was born, hoping that I will give him a different answer each time. I suspect he thinks I just pulled that year out of my ass, that 1977 can’t possibly be a real year that actually existed. Of course 1977 seems like a fictitious year if you were born in 2013 – like he was. To him it seems like some era before calendars were invented and not long after Adam met Eve. I bet he thinks that in 1977 I might have run into Judas at some point, tethering his donkey to an apple tree next to his small shop where he fixed locks.

“Hey, Juds.”

“Hey, Biks.”

“When do you stick it to Long Hair?”

“Workin’ on it.”

“Well, what’s taking so long, I thought it was already written?”

“A little matter of money, the chief priest wants to pay only 10 pieces of silver.”

“ Bloody hell. I wouldn’t sell my old blind donkey for that.”

“Yeah. But I hear they might be talking to James.”

“The son of Alpheus? Please. He wouldn’t do it. He’s yellow like his daddy.”

“What are those in your ears, anyway?”

“Apple Airpods?”

“An apple in your ear?”

“It’s beyond your time. Listen Juds, don’t take 10 pieces of silver, not enough to do the devil’s dirty work.”

Kim asks questions like, were there cars in 1977? What did people eat in 1977? (Each other. Or locusts.) What about pizza, was there pizza? What about aeroplanes? How did you go to school if your school didn’t have a school bus? [I crossed a hippo-infested river and then jumped on a donkey]. One time he asked me to show him photos of when I joined grade one on my phone. I laughed and told him, there were no mobile phones then. His eyes widened. “But then how did you talk to other people?”

“Landline.” I said.

“What’s a landline?”

“It’s a phone that you can’t leave the house with.”

“But it can take photos.”

“No. No photos. It’s just a phone that did one thing.”

“Oh.” Pause. “So you didn’t have photos when you were a baby?”

“I do. But they are in an album.”

“Where is the album?”

“My dad has it in the village.”

On and on and on it goes down a rabbit hole. So you have to stop it and you only stop it by asking a tougher question that they hate: “when was the last time you read that Kiswahili storybook I bought you?” Yeah. Turn the heat on them and escape.

Last year I interviewed a pleasant old woman in Iten who was born in 1916. [Gulp]. Wait, I think I have a photo somewhere in my landline.

Hang on…

We drove down a picturesque winding escarpment, into villages, past farms and green foliage and cows and to her most boma. It was nippy and fresh and the smell of woodsmoke hung in the air. I love woodsmoke.

To her left sat her 71 year old son who was my translator. You could tell how much he loves her by how he held her arm, how they giggled at the inside jokes they shared. Because she was half-deaf, he shouted my questions into her left ear, which was both hilarious and somewhat sad.

Amongst other things, I was curious about what sickness people suffered from when she was a little girl [was there homa?] and what killed people. She said fevers and wars killed people. You caught a fever and then someone speared you in the heart. [Not related and certainly not at the same time]. Her dad killed two people, she told us. These were enemies so they got what was coming to them. Men picked their spears and went to war. There was no room for cowardice. You fought for your village and your people and you died with your spear in your hand, like a man. Or sometimes you died from a fever. There was also cancer, she said. But it wasn’t called cancer. It was just a stubborn disease that the boiled roots and leaves couldn’t treat. Otherwise, people just didn’t die often. They lived and lived and lived and then when they got old they rolled over and died. You won’t believe what you will learn from people who have done time. People from another time.

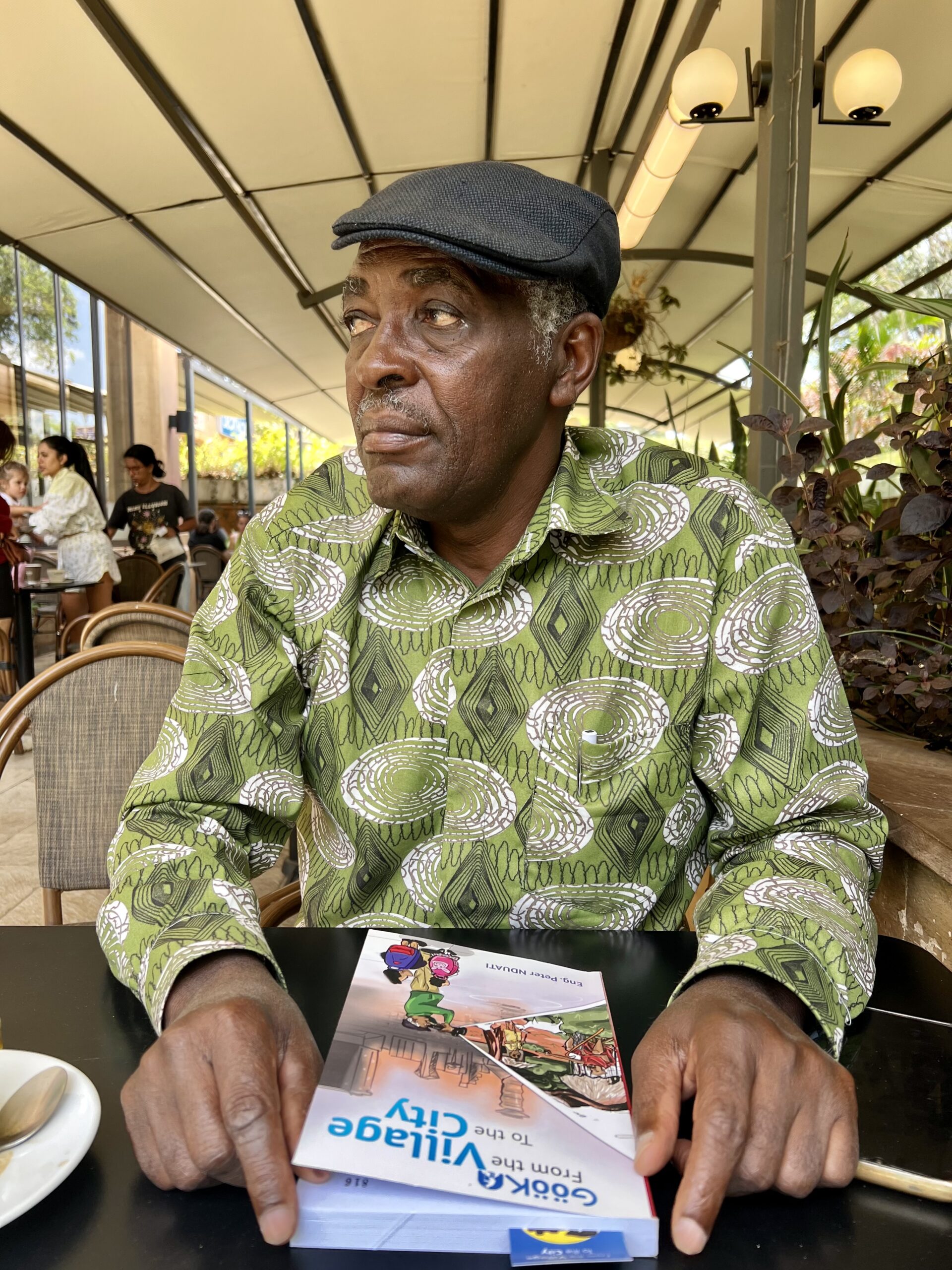

Yesterday I met up with a man who was born in 1953 and grew up under the big shadow of Mt Kenya. Of course I was going to ask him the one question you would be curious about; “what do you remember about the Mau-Mau?” Actually, that’s the first question I asked him after the usual niceties; hello engineer, how are you? You look well and taller than you looked on Zoom in 2021. Yeah the weather is a bit overcast today, it’s been a bit hot lately. Oh, nice to meet you, finally. Nice hat, by the way.

Then I segued into Mau-Mau.

He just stared at me. He didn’t say a word. He just gave me this long glare, which looked half admonishing and half contemplative. The question floated between us, deciding what it wanted to do with itself. Silence curled between us. He continued to stare at me; a dead stare. I didn’t want to look away from his glare, I couldn’t look away because that would have meant I was intimidated and you can’t be in the business of asking questions if you get intimidated. So we just held our stares. He had one one of those peaky blinder hats, casting a shadow over his eyes. His eyebrows had sprinkles of white on them. His eyes looked slightly curdled, like milk left on a counter, but held the promise of being cheeky. I hoped he found my eyes, at the very least beautiful. I have a white ring around my pupils that people who have looked deep in my eyes have asked, what’s that?

So we just looked into each other’s souls as all around us at Art Cafe, Karen, cups approached lips, knives sawed into food and laughter floated up from tables like smoke. Did I offend him with that question? I wondered as I looked into his dark pupils. Did that question arouse bad memories and open a Pandora’s box? What did I trigger? Was it too soon? He finally looked away and said, a little hesitantly,“I remember people coming from the forest, from the bush.” Pause. “Dreadlocked men. Long ones, reaching here. I was very young, maybe 5 years or even younger so it’s not very clear, these memories…”

“What time would they come from the forest,” I asked. “Was it under the cover of darkness, at dawn, during the day? What did they carry? Wooden guns? Spears? How was their temperament? ”

“They were suspicious and jumpy. These were men who had been released from the detention camps. There was a camp about 7kms from my village. I come from a village called Gacoco in Muranga. So they’d come during the day wearing very tattered clothes and long hair and reunite with their families. Those unions were always very sombre.”

“Were they regarded as heroes?”

Two creases folded the skin over his eyebrows. “I can’t recall. But I recall that these men came back broken. Nothing good came out of the detention camps because when you came out you were not the same. They were just changed; damaged and hurt. Some of these guys had been betrayed by people who knew them. So you can imagine their state, they never settled back fully. They had changed.”

Many men had been sent away to detention, he told me, and a lot of homes were run by women who stepped in to play the role. There were no men in a lot of homes. “Homes, villages became predominantly matriarchal. So this meant that the community was filled with very strong women, including my late mother who I looked up to because my dad had been detained in 1955. Most men during that time looked up to their mothers because there were no fathers to look up to.”

When his dad was released from the detention camp, he was a shadow of his former self. Before detention he worked for the railways but after his release he couldn’t secure any job, he was persona non grata and had to return to the village to stew silently. He was emptied of happiness. They had taken it all at the camp. He became withdrawn and sullen. He had ‘internal anger.’ And scores of returnees were like that, they couldn’t adjust, couldn’t relate to the new life they had returned to. And because this was the 1950s and they were men, they didn’t talk about how they felt with anybody [do they still?] They went about carrying pain and hurt and they transferred it to the people around them.

“How do you think that impacted boys like you,” I asked him, “being raised in matriarchal homes with these absent fathers?”

“Most problems in Central Province, at least according to my analysis, generate from this period of time. A time when sons were left without fathers, without father figures and mothers who, despite doing their very best under these very difficult circumstances, did not have all the answers for these growing boys. You understand?”

“Yeah.”

“And without answers, without male figures around them, most of them sought refuge in alcohol. Alcoholism in the central province is as a result of this time, boys lacking fatherly attention, guidance and mentorship, especially at crucial times when they were transitioning from boys to men. They had nobody to guide them, to look up to, so they were left to grow like trees in the forest.”

His milkshake and my black masala tea arrived. Our waiter was an agile and alert fellow called Dinda Bonvestus. I have never met anyone called Bonvestus in my life but I can bet this fella is either Luo or Catholic. And don’t pretend that you have met someone called Bonvestus. I have met Bonventure, yes [he was Tanzanian] but never Bonvestus. It’s a bombastic name. Bonvestus sounds like an investment product.

The man I’m having tea with is called Engineer Peter Nduati even though he is retired and isn’t doing any engineering at all. I also know people who are called Major so-and-so yet they are no longer in the military. My dad is still called Mwalimu. So I guess once an engineer, always an engineer. He’s an engineer of life now.

Engineer Nduati studied engineering at University of Nairobi then got a job with Nairobi City Council then hung out a shingle as a consulting engineer studying, designing and supervising roads in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana and Eritrea.

He was lucky because he had an older brother who provided the father figure he needed. “One time, when I was very young, I stumbled upon my brother’s book that he had left behind. It was written Makerere University. I was greatly curious about this place that my brother had gone to. I remember thinking, to leave the village, you have to study hard and join a university like Makerere, like my brother did. And because I wanted to be like him and leave the village I worked hard and joined Nairobi University.”

He’s long retired now. He has three children, two boys and a girl. The oldest boy is 39 and the youngest, a girl 23, is studying engineering in the UK. His sons are both doctors; a neurosurgeon and a radiologist. He has an empty nest now, living his best life with his wife. He’s a grandfather, a dotting one. [He talked about them a lot] I once asked an old man the difference between raising children and having grandchildren and he said, “children are investments, grandchildren are the interest on your investment.”

We drove down a picturesque winding escarpment, into villages, past farms and green foliage and cows and to her most boma. It was nippy and fresh and the smell of woodsmoke hung in the air. I love woodsmoke.

To her left sat her 71 year old son who was my translator. You could tell how much he loves her by how he held her arm, how they giggled at the inside jokes they shared. Because she was half-deaf, he shouted my questions into her left ear, which was both hilarious and somewhat sad.

Amongst other things, I was curious about what sickness people suffered from when she was a little girl [was there homa?] and what killed people. She said fevers and wars killed people. You caught a fever and then someone speared you in the heart. [Not related and certainly not at the same time]. Her dad killed two people, she told us. These were enemies so they got what was coming to them. Men picked their spears and went to war. There was no room for cowardice. You fought for your village and your people and you died with your spear in your hand, like a man. Or sometimes you died from a fever. There was also cancer, she said. But it wasn’t called cancer. It was just a stubborn disease that the boiled roots and leaves couldn’t treat. Otherwise, people just didn’t die often. They lived and lived and lived and then when they got old they rolled over and died. You won’t believe what you will learn from people who have done time. People from another time.

Yesterday I met up with a man who was born in 1953 and grew up under the big shadow of Mt Kenya. Of course I was going to ask him the one question you would be curious about; “what do you remember about the Mau-Mau?” Actually, that’s the first question I asked him after the usual niceties; hello engineer, how are you? You look well and taller than you looked on Zoom in 2021. Yeah the weather is a bit overcast today, it’s been a bit hot lately. Oh, nice to meet you, finally. Nice hat, by the way.

Then I segued into Mau-Mau.

He just stared at me. He didn’t say a word. He just gave me this long glare, which looked half admonishing and half contemplative. The question floated between us, deciding what it wanted to do with itself. Silence curled between us. He continued to stare at me; a dead stare. I didn’t want to look away from his glare, I couldn’t look away because that would have meant I was intimidated and you can’t be in the business of asking questions if you get intimidated. So we just held our stares. He had one one of those peaky blinder hats, casting a shadow over his eyes. His eyebrows had sprinkles of white on them. His eyes looked slightly curdled, like milk left on a counter, but held the promise of being cheeky. I hoped he found my eyes, at the very least beautiful. I have a white ring around my pupils that people who have looked deep in my eyes have asked, what’s that?

So we just looked into each other’s souls as all around us at Art Cafe, Karen, cups approached lips, knives sawed into food and laughter floated up from tables like smoke. Did I offend him with that question? I wondered as I looked into his dark pupils. Did that question arouse bad memories and open a Pandora’s box? What did I trigger? Was it too soon? He finally looked away and said, a little hesitantly,“I remember people coming from the forest, from the bush.” Pause. “Dreadlocked men. Long ones, reaching here. I was very young, maybe 5 years or even younger so it’s not very clear, these memories…”

“What time would they come from the forest,” I asked. “Was it under the cover of darkness, at dawn, during the day? What did they carry? Wooden guns? Spears? How was their temperament? ”

“They were suspicious and jumpy. These were men who had been released from the detention camps. There was a camp about 7kms from my village. I come from a village called Gacoco in Muranga. So they’d come during the day wearing very tattered clothes and long hair and reunite with their families. Those unions were always very sombre.”

“Were they regarded as heroes?”

Two creases folded the skin over his eyebrows. “I can’t recall. But I recall that these men came back broken. Nothing good came out of the detention camps because when you came out you were not the same. They were just changed; damaged and hurt. Some of these guys had been betrayed by people who knew them. So you can imagine their state, they never settled back fully. They had changed.”

Many men had been sent away to detention, he told me, and a lot of homes were run by women who stepped in to play the role. There were no men in a lot of homes. “Homes, villages became predominantly matriarchal. So this meant that the community was filled with very strong women, including my late mother who I looked up to because my dad had been detained in 1955. Most men during that time looked up to their mothers because there were no fathers to look up to.”

When his dad was released from the detention camp, he was a shadow of his former self. Before detention he worked for the railways but after his release he couldn’t secure any job, he was persona non grata and had to return to the village to stew silently. He was emptied of happiness. They had taken it all at the camp. He became withdrawn and sullen. He had ‘internal anger.’ And scores of returnees were like that, they couldn’t adjust, couldn’t relate to the new life they had returned to. And because this was the 1950s and they were men, they didn’t talk about how they felt with anybody [do they still?] They went about carrying pain and hurt and they transferred it to the people around them.

“How do you think that impacted boys like you,” I asked him, “being raised in matriarchal homes with these absent fathers?”

“Most problems in Central Province, at least according to my analysis, generate from this period of time. A time when sons were left without fathers, without father figures and mothers who, despite doing their very best under these very difficult circumstances, did not have all the answers for these growing boys. You understand?”

“Yeah.”

“And without answers, without male figures around them, most of them sought refuge in alcohol. Alcoholism in the central province is as a result of this time, boys lacking fatherly attention, guidance and mentorship, especially at crucial times when they were transitioning from boys to men. They had nobody to guide them, to look up to, so they were left to grow like trees in the forest.”

His milkshake and my black masala tea arrived. Our waiter was an agile and alert fellow called Dinda Bonvestus. I have never met anyone called Bonvestus in my life but I can bet this fella is either Luo or Catholic. And don’t pretend that you have met someone called Bonvestus. I have met Bonventure, yes [he was Tanzanian] but never Bonvestus. It’s a bombastic name. Bonvestus sounds like an investment product.

The man I’m having tea with is called Engineer Peter Nduati even though he is retired and isn’t doing any engineering at all. I also know people who are called Major so-and-so yet they are no longer in the military. My dad is still called Mwalimu. So I guess once an engineer, always an engineer. He’s an engineer of life now.

Engineer Nduati studied engineering at University of Nairobi then got a job with Nairobi City Council then hung out a shingle as a consulting engineer studying, designing and supervising roads in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana and Eritrea.

He was lucky because he had an older brother who provided the father figure he needed. “One time, when I was very young, I stumbled upon my brother’s book that he had left behind. It was written Makerere University. I was greatly curious about this place that my brother had gone to. I remember thinking, to leave the village, you have to study hard and join a university like Makerere, like my brother did. And because I wanted to be like him and leave the village I worked hard and joined Nairobi University.”

He’s long retired now. He has three children, two boys and a girl. The oldest boy is 39 and the youngest, a girl 23, is studying engineering in the UK. His sons are both doctors; a neurosurgeon and a radiologist. He has an empty nest now, living his best life with his wife. He’s a grandfather, a dotting one. [He talked about them a lot] I once asked an old man the difference between raising children and having grandchildren and he said, “children are investments, grandchildren are the interest on your investment.”

“Were you a great father?”

“I’m still a great father.” He said. “I think I have been a very good father.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I see how we relate and how other children relate with their parents. I’m very close with my children, but you can’t forge this closeness if you don’t put in the time. Time is the secret to great fatherhood. Time, time, time” he repeated. “That’s the most important thing children need from you. As a young engineer I deliberately made a decision not to go on sites away outside Nairobi when my colleagues were taking those jobs to make more money. This detached them from their children. Jobs do that. If you see them talking to their children now, you can’t believe that they are their children. There is a disconnect, because you made certain decisions that prioritised what you wanted over time with your children. Of course that gave them a better life at that time, a bigger car or house, but at the expense of their relationship with their children.”

Earlier in their marriage, his wife left for further studies abroad for nine months. “My children were very young. I would leave work and take lunch home every day. In the evening I would go straight home and cook and see them in bed.” Teenage was hard, but “you have to find a way to connect with them so I would go and shoot pool with my sons, so that they don’t feel deprived of something. My daughter has a 10 and 13 year gap with her brothers, so they raised her. They changed nappies and what not. This made them very close but also prepared them to be fathers themselves. And I think they are great fathers.”

His fatherhood mentality is greatly informed by a book he read before his children were born. “My wife is a paediatrician and she had this book in the house called The Common Sense Book of Baby and childcare by Benjamin Spock.” he leaned across the table,” nobody is born knowing what to do, you can’t do things right without reading and learning from others experiences.”

He met his wife in Canada in the late 1970s. He probably had a big afro and wide-ankled pants and writhed on the dancefloor in a disco. [Yeah, back in the day people went to the disco. The disco sounds hella serious] The city council had sponsored his education to the US, and this one time he went to Ottawa for the weekend to visit his boy called Muia Wachira. They were thick as thieves. It was summer. Muia used to run marathons in Ottawa, they both loved running, so on a Saturday they went running and then later they went to a dinner party thrown at the Kenyan embassy’s counsellor’s residence because Muia was that guy. Muia was the Kevo of their generation. He knew people and happening things. A guy of form.

Unbeknownst to him the party was in honour of this lady who was a medical student on an exchange program in Montreal, also visiting for the weekend. Her uncle was throwing the party or something. They met at this party. He must have seen her across the table, slim, elegant, saying something smart and he leaned in and whispered to Muia, “who’s that chic?”

“That’s Ciru. Ruth Wanjiru,” Muia said, his dessert spoon in his hand. “Why, you dig her?”

“Yeah, she fine.” He said.

The next day they all went to this thing he called The Trooping of The Colour event which I didn’t know about and didn’t want to interrupt the story by asking him, ‘waz that?” So I googled it later in my own free time so that you don’t have to. It’s a fanfare event to mark the birthday of the British sovereign. So,1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses, a jamboree of sorts, a spectacle. Engineer Nduati was the cameraman who took pictures and after the event, Ruth from the party told him, “make sure you send me those photos when we get back to Kenya.”

But Engineer was a bit slow. It took his boy Muia telling him, “boss, that chick asked about the photos.”

“Oh, I’m yet to process the film.”

“It’s not about the damn photos. She is asking about you. What are you doing?! Si you make your move.” So he patted his afro and said, OK, hold my beer. The rest is history. They are happily married now, 40 years in July.

“It wasn’t love at first sight. It developed organically over time.” he told me, “Sometimes love isn’t a big explosion. Sometimes it’s a small spark that causes a small fire and which grows and grows till it is big.”

“So, 40 years. So what’s the secret to a long happy marriage?”

“I have had a good marriage because I believe in what Kahil Gibran believes about marriage,” he said.

“What does Kahil Gibran believe about marriage?”

“That your wife doesn’t belong to you.” He said. “Gabrin believes that you and your wife are like two trees in a forest growing next to each other. One tree is protecting the other on one side from winds and storms while the other is doing the same from the other side. But they remain separate and rooted next to each other. Co-existing while being different.”

“I like that.” I said. “I really do.”

“Exactly. Your wife doesn’t belong to you!” he said. “You have to give ladies their space to be who they are.”

I wrote on my notes; give the tree space to be the tree she wants to be. Then I added under that sentence: Two trees. Forest. Different monkeys.

“But surely,” I said looking up from my childish literature, “you weren’t born knowing all these. You were married at 27, you must have fumbled a lot before you discovered these gems, yes?”

Yes, he said. Then he told me that his dad was polygamous. His mom was the first wife, which meant she wasn’t as favoured as the second wife. “You have to learn from every experience and I learnt from watching my father and his two wives. I learnt what not to do by watching what he was doing.”

“What does your wife complain about most concerning you?” I asked.

“That I don’t let her speak.”

“You are always talking.”

He laughed. “Yeah, she always says, please let me speak! That I don’t give her opinions as much thought as I should. But my wife is such a lovely lady, we have a good marriage. In fact, she dropped me off here, she is seated somewhere in this restaurant. Do you want to meet her?”

“I’d love to!” I shrieked. “By the way, what are you better at, being a dad or a husband?”

No sooner had the word husband left my lips than he said, “definitely a husband! I’m a better husband than I am a dad. You know why?”

“Why?”

“Because fatherhood is a duty and a responsibility but being a husband is a commitment. It’s harder to be a husband so I intentionally put in more daily. Here is my theory about living together as a husband and wife.”

I wrote in my Notes, BIG BANG ENGINEER THEORY.

“First, you don’t have to win every argument. Second. The rule, my rule at least, is always that the more dominant partner in the marriage has to give more than the less dominant partner. If your opinions are the loudest or strongest you have to sacrifice more for the marriage. And that person has to keep giving a bit of themselves every day to balance everything out.”

And lesson on money, Engineer?

“Spend ONLY on what you need, never what you want because you will never get enough of what you want. It’s a dark hole that keeps taking and taking.”

We drained our beverages and went to find his wife. She was in a corner working. She stood up. She was tall. A tall paediatrician and a teacher. She’s a professor at UoN. Professor Ruth Wanjiru. I could tell the Engineer was proud of her by the way he introduced her. How he looked at her. Like she was his secret weapon, his Ace card. Prof was gracious and said other nice things about him (I’m proud of him) and about me. “He talks very highly of you,” she said, “thanks for inspiring him to write.”

Engineer Nduati attended my writing masterclass in 2021. He’s the oldest male to attend my class. [The oldest female and most distinguished persona to attend is the Chief Justice Martha Koome who should have started writing her book but no pressure]. Engineer Nduati class was paid for by one of his daughters-in-law and his daughter, who felt like he had words in him, based on bristling emails he wrote to his daughter and to a common email group they have.

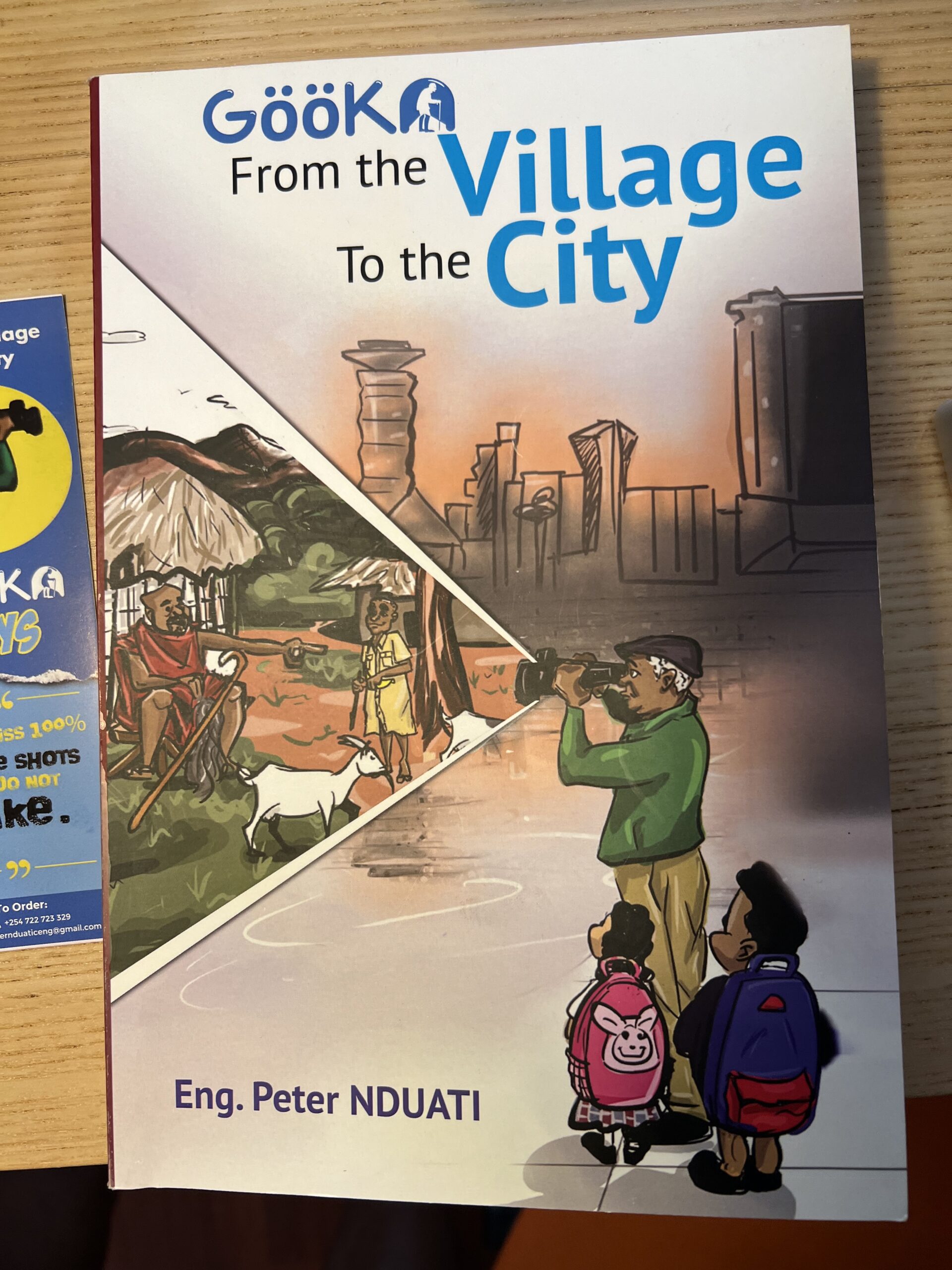

His book is called Gookaa From The Village To The City. It’s wild like Gooka’s hat. To show you what kind of a wacky Gooka engineer is, the book starts like this.

I was born in the city, like some of you. I survived the Mau Mau, unlike many of you. I grew up in the village, like some of you. I fought other boys, like many of you. I feared the girls, like many boys do. I slept hungry like many still do. School had good memories but sometimes a bore, or so I thought. Once I was young and full of life, like many you see. I never will grow old, said I to self. A grandfather was as archaic as my mind would say. From a baby to a boy to a father, from a father to a grandfather, a gooka. Gooka I am today, Gooka tomorrow you will be.

“Were you a great father?”

“I’m still a great father.” He said. “I think I have been a very good father.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I see how we relate and how other children relate with their parents. I’m very close with my children, but you can’t forge this closeness if you don’t put in the time. Time is the secret to great fatherhood. Time, time, time” he repeated. “That’s the most important thing children need from you. As a young engineer I deliberately made a decision not to go on sites away outside Nairobi when my colleagues were taking those jobs to make more money. This detached them from their children. Jobs do that. If you see them talking to their children now, you can’t believe that they are their children. There is a disconnect, because you made certain decisions that prioritised what you wanted over time with your children. Of course that gave them a better life at that time, a bigger car or house, but at the expense of their relationship with their children.”

Earlier in their marriage, his wife left for further studies abroad for nine months. “My children were very young. I would leave work and take lunch home every day. In the evening I would go straight home and cook and see them in bed.” Teenage was hard, but “you have to find a way to connect with them so I would go and shoot pool with my sons, so that they don’t feel deprived of something. My daughter has a 10 and 13 year gap with her brothers, so they raised her. They changed nappies and what not. This made them very close but also prepared them to be fathers themselves. And I think they are great fathers.”

His fatherhood mentality is greatly informed by a book he read before his children were born. “My wife is a paediatrician and she had this book in the house called The Common Sense Book of Baby and childcare by Benjamin Spock.” he leaned across the table,” nobody is born knowing what to do, you can’t do things right without reading and learning from others experiences.”

He met his wife in Canada in the late 1970s. He probably had a big afro and wide-ankled pants and writhed on the dancefloor in a disco. [Yeah, back in the day people went to the disco. The disco sounds hella serious] The city council had sponsored his education to the US, and this one time he went to Ottawa for the weekend to visit his boy called Muia Wachira. They were thick as thieves. It was summer. Muia used to run marathons in Ottawa, they both loved running, so on a Saturday they went running and then later they went to a dinner party thrown at the Kenyan embassy’s counsellor’s residence because Muia was that guy. Muia was the Kevo of their generation. He knew people and happening things. A guy of form.

Unbeknownst to him the party was in honour of this lady who was a medical student on an exchange program in Montreal, also visiting for the weekend. Her uncle was throwing the party or something. They met at this party. He must have seen her across the table, slim, elegant, saying something smart and he leaned in and whispered to Muia, “who’s that chic?”

“That’s Ciru. Ruth Wanjiru,” Muia said, his dessert spoon in his hand. “Why, you dig her?”

“Yeah, she fine.” He said.

The next day they all went to this thing he called The Trooping of The Colour event which I didn’t know about and didn’t want to interrupt the story by asking him, ‘waz that?” So I googled it later in my own free time so that you don’t have to. It’s a fanfare event to mark the birthday of the British sovereign. So,1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses, a jamboree of sorts, a spectacle. Engineer Nduati was the cameraman who took pictures and after the event, Ruth from the party told him, “make sure you send me those photos when we get back to Kenya.”

But Engineer was a bit slow. It took his boy Muia telling him, “boss, that chick asked about the photos.”

“Oh, I’m yet to process the film.”

“It’s not about the damn photos. She is asking about you. What are you doing?! Si you make your move.” So he patted his afro and said, OK, hold my beer. The rest is history. They are happily married now, 40 years in July.

“It wasn’t love at first sight. It developed organically over time.” he told me, “Sometimes love isn’t a big explosion. Sometimes it’s a small spark that causes a small fire and which grows and grows till it is big.”

“So, 40 years. So what’s the secret to a long happy marriage?”

“I have had a good marriage because I believe in what Kahil Gibran believes about marriage,” he said.

“What does Kahil Gibran believe about marriage?”

“That your wife doesn’t belong to you.” He said. “Gabrin believes that you and your wife are like two trees in a forest growing next to each other. One tree is protecting the other on one side from winds and storms while the other is doing the same from the other side. But they remain separate and rooted next to each other. Co-existing while being different.”

“I like that.” I said. “I really do.”

“Exactly. Your wife doesn’t belong to you!” he said. “You have to give ladies their space to be who they are.”

I wrote on my notes; give the tree space to be the tree she wants to be. Then I added under that sentence: Two trees. Forest. Different monkeys.

“But surely,” I said looking up from my childish literature, “you weren’t born knowing all these. You were married at 27, you must have fumbled a lot before you discovered these gems, yes?”

Yes, he said. Then he told me that his dad was polygamous. His mom was the first wife, which meant she wasn’t as favoured as the second wife. “You have to learn from every experience and I learnt from watching my father and his two wives. I learnt what not to do by watching what he was doing.”

“What does your wife complain about most concerning you?” I asked.

“That I don’t let her speak.”

“You are always talking.”

He laughed. “Yeah, she always says, please let me speak! That I don’t give her opinions as much thought as I should. But my wife is such a lovely lady, we have a good marriage. In fact, she dropped me off here, she is seated somewhere in this restaurant. Do you want to meet her?”

“I’d love to!” I shrieked. “By the way, what are you better at, being a dad or a husband?”

No sooner had the word husband left my lips than he said, “definitely a husband! I’m a better husband than I am a dad. You know why?”

“Why?”

“Because fatherhood is a duty and a responsibility but being a husband is a commitment. It’s harder to be a husband so I intentionally put in more daily. Here is my theory about living together as a husband and wife.”

I wrote in my Notes, BIG BANG ENGINEER THEORY.

“First, you don’t have to win every argument. Second. The rule, my rule at least, is always that the more dominant partner in the marriage has to give more than the less dominant partner. If your opinions are the loudest or strongest you have to sacrifice more for the marriage. And that person has to keep giving a bit of themselves every day to balance everything out.”

And lesson on money, Engineer?

“Spend ONLY on what you need, never what you want because you will never get enough of what you want. It’s a dark hole that keeps taking and taking.”

We drained our beverages and went to find his wife. She was in a corner working. She stood up. She was tall. A tall paediatrician and a teacher. She’s a professor at UoN. Professor Ruth Wanjiru. I could tell the Engineer was proud of her by the way he introduced her. How he looked at her. Like she was his secret weapon, his Ace card. Prof was gracious and said other nice things about him (I’m proud of him) and about me. “He talks very highly of you,” she said, “thanks for inspiring him to write.”

Engineer Nduati attended my writing masterclass in 2021. He’s the oldest male to attend my class. [The oldest female and most distinguished persona to attend is the Chief Justice Martha Koome who should have started writing her book but no pressure]. Engineer Nduati class was paid for by one of his daughters-in-law and his daughter, who felt like he had words in him, based on bristling emails he wrote to his daughter and to a common email group they have.

His book is called Gookaa From The Village To The City. It’s wild like Gooka’s hat. To show you what kind of a wacky Gooka engineer is, the book starts like this.

I was born in the city, like some of you. I survived the Mau Mau, unlike many of you. I grew up in the village, like some of you. I fought other boys, like many of you. I feared the girls, like many boys do. I slept hungry like many still do. School had good memories but sometimes a bore, or so I thought. Once I was young and full of life, like many you see. I never will grow old, said I to self. A grandfather was as archaic as my mind would say. From a baby to a boy to a father, from a father to a grandfather, a gooka. Gooka I am today, Gooka tomorrow you will be.

Then off he launches into 290 pages of Gooka talk. The back has a picture of him in 2021 looking grim. The next photo is him in 1967 standing next to signage of his high school, alma mater, Njiiri School, ironically named after chief Njiiri, a collaborator during the struggle. [He told me how Njiiri used to fly over the village in a government helicopter saying how there will never be independence]

“I am grandfather, I jog, have a limp, a missing molar, white hair and my eyesight,: he writes in the back sleeve of that book. “Look at my pictures again. In 1967 I was not smiling, like Fermat’s theorem in mathematics, which took 200 years to prove, can you decipher why I am not smiling in not more than five words, and email your answer to [email protected] The first 100 correct answers get a free autographed copy of the book. [Government taxes and postage on you.]

Ha-ha. Like I said, a wacky gooka.

He also has a children’s colouring book. [I bought this one, the other one was an ahsante]. Kim should be able to enjoy the stories in there which come with lessons. His book also has a Braille version which he showed me. He also has numerous bookmarks with numerous messages like ‘you miss 100% of the shots you do not take” and behind a road safety message.

Retirement for who? Gooka is busy shaking the bushes, at what 69? I’m particularly proud that he has accomplished what he said he would do during the writing masterclass; to write a book. I’m very impressed because writing a book can be a beautiful but daunting commitment.

**

The first writing masterclass this year is at the end of March. Register HERE.

Note: I give homework in those classes.

Then off he launches into 290 pages of Gooka talk. The back has a picture of him in 2021 looking grim. The next photo is him in 1967 standing next to signage of his high school, alma mater, Njiiri School, ironically named after chief Njiiri, a collaborator during the struggle. [He told me how Njiiri used to fly over the village in a government helicopter saying how there will never be independence]

“I am grandfather, I jog, have a limp, a missing molar, white hair and my eyesight,: he writes in the back sleeve of that book. “Look at my pictures again. In 1967 I was not smiling, like Fermat’s theorem in mathematics, which took 200 years to prove, can you decipher why I am not smiling in not more than five words, and email your answer to [email protected] The first 100 correct answers get a free autographed copy of the book. [Government taxes and postage on you.]

Ha-ha. Like I said, a wacky gooka.

He also has a children’s colouring book. [I bought this one, the other one was an ahsante]. Kim should be able to enjoy the stories in there which come with lessons. His book also has a Braille version which he showed me. He also has numerous bookmarks with numerous messages like ‘you miss 100% of the shots you do not take” and behind a road safety message.

Retirement for who? Gooka is busy shaking the bushes, at what 69? I’m particularly proud that he has accomplished what he said he would do during the writing masterclass; to write a book. I’m very impressed because writing a book can be a beautiful but daunting commitment.

**

The first writing masterclass this year is at the end of March. Register HERE.

Note: I give homework in those classes.

We drove down a picturesque winding escarpment, into villages, past farms and green foliage and cows and to her most boma. It was nippy and fresh and the smell of woodsmoke hung in the air. I love woodsmoke.

To her left sat her 71 year old son who was my translator. You could tell how much he loves her by how he held her arm, how they giggled at the inside jokes they shared. Because she was half-deaf, he shouted my questions into her left ear, which was both hilarious and somewhat sad.

Amongst other things, I was curious about what sickness people suffered from when she was a little girl [was there homa?] and what killed people. She said fevers and wars killed people. You caught a fever and then someone speared you in the heart. [Not related and certainly not at the same time]. Her dad killed two people, she told us. These were enemies so they got what was coming to them. Men picked their spears and went to war. There was no room for cowardice. You fought for your village and your people and you died with your spear in your hand, like a man. Or sometimes you died from a fever. There was also cancer, she said. But it wasn’t called cancer. It was just a stubborn disease that the boiled roots and leaves couldn’t treat. Otherwise, people just didn’t die often. They lived and lived and lived and then when they got old they rolled over and died. You won’t believe what you will learn from people who have done time. People from another time.

Yesterday I met up with a man who was born in 1953 and grew up under the big shadow of Mt Kenya. Of course I was going to ask him the one question you would be curious about; “what do you remember about the Mau-Mau?” Actually, that’s the first question I asked him after the usual niceties; hello engineer, how are you? You look well and taller than you looked on Zoom in 2021. Yeah the weather is a bit overcast today, it’s been a bit hot lately. Oh, nice to meet you, finally. Nice hat, by the way.

Then I segued into Mau-Mau.

He just stared at me. He didn’t say a word. He just gave me this long glare, which looked half admonishing and half contemplative. The question floated between us, deciding what it wanted to do with itself. Silence curled between us. He continued to stare at me; a dead stare. I didn’t want to look away from his glare, I couldn’t look away because that would have meant I was intimidated and you can’t be in the business of asking questions if you get intimidated. So we just held our stares. He had one one of those peaky blinder hats, casting a shadow over his eyes. His eyebrows had sprinkles of white on them. His eyes looked slightly curdled, like milk left on a counter, but held the promise of being cheeky. I hoped he found my eyes, at the very least beautiful. I have a white ring around my pupils that people who have looked deep in my eyes have asked, what’s that?

So we just looked into each other’s souls as all around us at Art Cafe, Karen, cups approached lips, knives sawed into food and laughter floated up from tables like smoke. Did I offend him with that question? I wondered as I looked into his dark pupils. Did that question arouse bad memories and open a Pandora’s box? What did I trigger? Was it too soon? He finally looked away and said, a little hesitantly,“I remember people coming from the forest, from the bush.” Pause. “Dreadlocked men. Long ones, reaching here. I was very young, maybe 5 years or even younger so it’s not very clear, these memories…”

“What time would they come from the forest,” I asked. “Was it under the cover of darkness, at dawn, during the day? What did they carry? Wooden guns? Spears? How was their temperament? ”

“They were suspicious and jumpy. These were men who had been released from the detention camps. There was a camp about 7kms from my village. I come from a village called Gacoco in Muranga. So they’d come during the day wearing very tattered clothes and long hair and reunite with their families. Those unions were always very sombre.”

“Were they regarded as heroes?”

Two creases folded the skin over his eyebrows. “I can’t recall. But I recall that these men came back broken. Nothing good came out of the detention camps because when you came out you were not the same. They were just changed; damaged and hurt. Some of these guys had been betrayed by people who knew them. So you can imagine their state, they never settled back fully. They had changed.”

Many men had been sent away to detention, he told me, and a lot of homes were run by women who stepped in to play the role. There were no men in a lot of homes. “Homes, villages became predominantly matriarchal. So this meant that the community was filled with very strong women, including my late mother who I looked up to because my dad had been detained in 1955. Most men during that time looked up to their mothers because there were no fathers to look up to.”

When his dad was released from the detention camp, he was a shadow of his former self. Before detention he worked for the railways but after his release he couldn’t secure any job, he was persona non grata and had to return to the village to stew silently. He was emptied of happiness. They had taken it all at the camp. He became withdrawn and sullen. He had ‘internal anger.’ And scores of returnees were like that, they couldn’t adjust, couldn’t relate to the new life they had returned to. And because this was the 1950s and they were men, they didn’t talk about how they felt with anybody [do they still?] They went about carrying pain and hurt and they transferred it to the people around them.

“How do you think that impacted boys like you,” I asked him, “being raised in matriarchal homes with these absent fathers?”

“Most problems in Central Province, at least according to my analysis, generate from this period of time. A time when sons were left without fathers, without father figures and mothers who, despite doing their very best under these very difficult circumstances, did not have all the answers for these growing boys. You understand?”

“Yeah.”

“And without answers, without male figures around them, most of them sought refuge in alcohol. Alcoholism in the central province is as a result of this time, boys lacking fatherly attention, guidance and mentorship, especially at crucial times when they were transitioning from boys to men. They had nobody to guide them, to look up to, so they were left to grow like trees in the forest.”

His milkshake and my black masala tea arrived. Our waiter was an agile and alert fellow called Dinda Bonvestus. I have never met anyone called Bonvestus in my life but I can bet this fella is either Luo or Catholic. And don’t pretend that you have met someone called Bonvestus. I have met Bonventure, yes [he was Tanzanian] but never Bonvestus. It’s a bombastic name. Bonvestus sounds like an investment product.

The man I’m having tea with is called Engineer Peter Nduati even though he is retired and isn’t doing any engineering at all. I also know people who are called Major so-and-so yet they are no longer in the military. My dad is still called Mwalimu. So I guess once an engineer, always an engineer. He’s an engineer of life now.

Engineer Nduati studied engineering at University of Nairobi then got a job with Nairobi City Council then hung out a shingle as a consulting engineer studying, designing and supervising roads in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana and Eritrea.

He was lucky because he had an older brother who provided the father figure he needed. “One time, when I was very young, I stumbled upon my brother’s book that he had left behind. It was written Makerere University. I was greatly curious about this place that my brother had gone to. I remember thinking, to leave the village, you have to study hard and join a university like Makerere, like my brother did. And because I wanted to be like him and leave the village I worked hard and joined Nairobi University.”

He’s long retired now. He has three children, two boys and a girl. The oldest boy is 39 and the youngest, a girl 23, is studying engineering in the UK. His sons are both doctors; a neurosurgeon and a radiologist. He has an empty nest now, living his best life with his wife. He’s a grandfather, a dotting one. [He talked about them a lot] I once asked an old man the difference between raising children and having grandchildren and he said, “children are investments, grandchildren are the interest on your investment.”

We drove down a picturesque winding escarpment, into villages, past farms and green foliage and cows and to her most boma. It was nippy and fresh and the smell of woodsmoke hung in the air. I love woodsmoke.

To her left sat her 71 year old son who was my translator. You could tell how much he loves her by how he held her arm, how they giggled at the inside jokes they shared. Because she was half-deaf, he shouted my questions into her left ear, which was both hilarious and somewhat sad.

Amongst other things, I was curious about what sickness people suffered from when she was a little girl [was there homa?] and what killed people. She said fevers and wars killed people. You caught a fever and then someone speared you in the heart. [Not related and certainly not at the same time]. Her dad killed two people, she told us. These were enemies so they got what was coming to them. Men picked their spears and went to war. There was no room for cowardice. You fought for your village and your people and you died with your spear in your hand, like a man. Or sometimes you died from a fever. There was also cancer, she said. But it wasn’t called cancer. It was just a stubborn disease that the boiled roots and leaves couldn’t treat. Otherwise, people just didn’t die often. They lived and lived and lived and then when they got old they rolled over and died. You won’t believe what you will learn from people who have done time. People from another time.

Yesterday I met up with a man who was born in 1953 and grew up under the big shadow of Mt Kenya. Of course I was going to ask him the one question you would be curious about; “what do you remember about the Mau-Mau?” Actually, that’s the first question I asked him after the usual niceties; hello engineer, how are you? You look well and taller than you looked on Zoom in 2021. Yeah the weather is a bit overcast today, it’s been a bit hot lately. Oh, nice to meet you, finally. Nice hat, by the way.

Then I segued into Mau-Mau.

He just stared at me. He didn’t say a word. He just gave me this long glare, which looked half admonishing and half contemplative. The question floated between us, deciding what it wanted to do with itself. Silence curled between us. He continued to stare at me; a dead stare. I didn’t want to look away from his glare, I couldn’t look away because that would have meant I was intimidated and you can’t be in the business of asking questions if you get intimidated. So we just held our stares. He had one one of those peaky blinder hats, casting a shadow over his eyes. His eyebrows had sprinkles of white on them. His eyes looked slightly curdled, like milk left on a counter, but held the promise of being cheeky. I hoped he found my eyes, at the very least beautiful. I have a white ring around my pupils that people who have looked deep in my eyes have asked, what’s that?

So we just looked into each other’s souls as all around us at Art Cafe, Karen, cups approached lips, knives sawed into food and laughter floated up from tables like smoke. Did I offend him with that question? I wondered as I looked into his dark pupils. Did that question arouse bad memories and open a Pandora’s box? What did I trigger? Was it too soon? He finally looked away and said, a little hesitantly,“I remember people coming from the forest, from the bush.” Pause. “Dreadlocked men. Long ones, reaching here. I was very young, maybe 5 years or even younger so it’s not very clear, these memories…”

“What time would they come from the forest,” I asked. “Was it under the cover of darkness, at dawn, during the day? What did they carry? Wooden guns? Spears? How was their temperament? ”

“They were suspicious and jumpy. These were men who had been released from the detention camps. There was a camp about 7kms from my village. I come from a village called Gacoco in Muranga. So they’d come during the day wearing very tattered clothes and long hair and reunite with their families. Those unions were always very sombre.”

“Were they regarded as heroes?”

Two creases folded the skin over his eyebrows. “I can’t recall. But I recall that these men came back broken. Nothing good came out of the detention camps because when you came out you were not the same. They were just changed; damaged and hurt. Some of these guys had been betrayed by people who knew them. So you can imagine their state, they never settled back fully. They had changed.”

Many men had been sent away to detention, he told me, and a lot of homes were run by women who stepped in to play the role. There were no men in a lot of homes. “Homes, villages became predominantly matriarchal. So this meant that the community was filled with very strong women, including my late mother who I looked up to because my dad had been detained in 1955. Most men during that time looked up to their mothers because there were no fathers to look up to.”

When his dad was released from the detention camp, he was a shadow of his former self. Before detention he worked for the railways but after his release he couldn’t secure any job, he was persona non grata and had to return to the village to stew silently. He was emptied of happiness. They had taken it all at the camp. He became withdrawn and sullen. He had ‘internal anger.’ And scores of returnees were like that, they couldn’t adjust, couldn’t relate to the new life they had returned to. And because this was the 1950s and they were men, they didn’t talk about how they felt with anybody [do they still?] They went about carrying pain and hurt and they transferred it to the people around them.

“How do you think that impacted boys like you,” I asked him, “being raised in matriarchal homes with these absent fathers?”

“Most problems in Central Province, at least according to my analysis, generate from this period of time. A time when sons were left without fathers, without father figures and mothers who, despite doing their very best under these very difficult circumstances, did not have all the answers for these growing boys. You understand?”

“Yeah.”

“And without answers, without male figures around them, most of them sought refuge in alcohol. Alcoholism in the central province is as a result of this time, boys lacking fatherly attention, guidance and mentorship, especially at crucial times when they were transitioning from boys to men. They had nobody to guide them, to look up to, so they were left to grow like trees in the forest.”

His milkshake and my black masala tea arrived. Our waiter was an agile and alert fellow called Dinda Bonvestus. I have never met anyone called Bonvestus in my life but I can bet this fella is either Luo or Catholic. And don’t pretend that you have met someone called Bonvestus. I have met Bonventure, yes [he was Tanzanian] but never Bonvestus. It’s a bombastic name. Bonvestus sounds like an investment product.

The man I’m having tea with is called Engineer Peter Nduati even though he is retired and isn’t doing any engineering at all. I also know people who are called Major so-and-so yet they are no longer in the military. My dad is still called Mwalimu. So I guess once an engineer, always an engineer. He’s an engineer of life now.

Engineer Nduati studied engineering at University of Nairobi then got a job with Nairobi City Council then hung out a shingle as a consulting engineer studying, designing and supervising roads in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana and Eritrea.

He was lucky because he had an older brother who provided the father figure he needed. “One time, when I was very young, I stumbled upon my brother’s book that he had left behind. It was written Makerere University. I was greatly curious about this place that my brother had gone to. I remember thinking, to leave the village, you have to study hard and join a university like Makerere, like my brother did. And because I wanted to be like him and leave the village I worked hard and joined Nairobi University.”

He’s long retired now. He has three children, two boys and a girl. The oldest boy is 39 and the youngest, a girl 23, is studying engineering in the UK. His sons are both doctors; a neurosurgeon and a radiologist. He has an empty nest now, living his best life with his wife. He’s a grandfather, a dotting one. [He talked about them a lot] I once asked an old man the difference between raising children and having grandchildren and he said, “children are investments, grandchildren are the interest on your investment.”

“Were you a great father?”

“I’m still a great father.” He said. “I think I have been a very good father.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I see how we relate and how other children relate with their parents. I’m very close with my children, but you can’t forge this closeness if you don’t put in the time. Time is the secret to great fatherhood. Time, time, time” he repeated. “That’s the most important thing children need from you. As a young engineer I deliberately made a decision not to go on sites away outside Nairobi when my colleagues were taking those jobs to make more money. This detached them from their children. Jobs do that. If you see them talking to their children now, you can’t believe that they are their children. There is a disconnect, because you made certain decisions that prioritised what you wanted over time with your children. Of course that gave them a better life at that time, a bigger car or house, but at the expense of their relationship with their children.”

Earlier in their marriage, his wife left for further studies abroad for nine months. “My children were very young. I would leave work and take lunch home every day. In the evening I would go straight home and cook and see them in bed.” Teenage was hard, but “you have to find a way to connect with them so I would go and shoot pool with my sons, so that they don’t feel deprived of something. My daughter has a 10 and 13 year gap with her brothers, so they raised her. They changed nappies and what not. This made them very close but also prepared them to be fathers themselves. And I think they are great fathers.”

His fatherhood mentality is greatly informed by a book he read before his children were born. “My wife is a paediatrician and she had this book in the house called The Common Sense Book of Baby and childcare by Benjamin Spock.” he leaned across the table,” nobody is born knowing what to do, you can’t do things right without reading and learning from others experiences.”

He met his wife in Canada in the late 1970s. He probably had a big afro and wide-ankled pants and writhed on the dancefloor in a disco. [Yeah, back in the day people went to the disco. The disco sounds hella serious] The city council had sponsored his education to the US, and this one time he went to Ottawa for the weekend to visit his boy called Muia Wachira. They were thick as thieves. It was summer. Muia used to run marathons in Ottawa, they both loved running, so on a Saturday they went running and then later they went to a dinner party thrown at the Kenyan embassy’s counsellor’s residence because Muia was that guy. Muia was the Kevo of their generation. He knew people and happening things. A guy of form.

Unbeknownst to him the party was in honour of this lady who was a medical student on an exchange program in Montreal, also visiting for the weekend. Her uncle was throwing the party or something. They met at this party. He must have seen her across the table, slim, elegant, saying something smart and he leaned in and whispered to Muia, “who’s that chic?”

“That’s Ciru. Ruth Wanjiru,” Muia said, his dessert spoon in his hand. “Why, you dig her?”

“Yeah, she fine.” He said.

The next day they all went to this thing he called The Trooping of The Colour event which I didn’t know about and didn’t want to interrupt the story by asking him, ‘waz that?” So I googled it later in my own free time so that you don’t have to. It’s a fanfare event to mark the birthday of the British sovereign. So,1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses, a jamboree of sorts, a spectacle. Engineer Nduati was the cameraman who took pictures and after the event, Ruth from the party told him, “make sure you send me those photos when we get back to Kenya.”

But Engineer was a bit slow. It took his boy Muia telling him, “boss, that chick asked about the photos.”

“Oh, I’m yet to process the film.”

“It’s not about the damn photos. She is asking about you. What are you doing?! Si you make your move.” So he patted his afro and said, OK, hold my beer. The rest is history. They are happily married now, 40 years in July.

“It wasn’t love at first sight. It developed organically over time.” he told me, “Sometimes love isn’t a big explosion. Sometimes it’s a small spark that causes a small fire and which grows and grows till it is big.”

“So, 40 years. So what’s the secret to a long happy marriage?”

“I have had a good marriage because I believe in what Kahil Gibran believes about marriage,” he said.

“What does Kahil Gibran believe about marriage?”

“That your wife doesn’t belong to you.” He said. “Gabrin believes that you and your wife are like two trees in a forest growing next to each other. One tree is protecting the other on one side from winds and storms while the other is doing the same from the other side. But they remain separate and rooted next to each other. Co-existing while being different.”

“I like that.” I said. “I really do.”

“Exactly. Your wife doesn’t belong to you!” he said. “You have to give ladies their space to be who they are.”

I wrote on my notes; give the tree space to be the tree she wants to be. Then I added under that sentence: Two trees. Forest. Different monkeys.

“But surely,” I said looking up from my childish literature, “you weren’t born knowing all these. You were married at 27, you must have fumbled a lot before you discovered these gems, yes?”

Yes, he said. Then he told me that his dad was polygamous. His mom was the first wife, which meant she wasn’t as favoured as the second wife. “You have to learn from every experience and I learnt from watching my father and his two wives. I learnt what not to do by watching what he was doing.”

“What does your wife complain about most concerning you?” I asked.

“That I don’t let her speak.”

“You are always talking.”

He laughed. “Yeah, she always says, please let me speak! That I don’t give her opinions as much thought as I should. But my wife is such a lovely lady, we have a good marriage. In fact, she dropped me off here, she is seated somewhere in this restaurant. Do you want to meet her?”

“I’d love to!” I shrieked. “By the way, what are you better at, being a dad or a husband?”

No sooner had the word husband left my lips than he said, “definitely a husband! I’m a better husband than I am a dad. You know why?”

“Why?”

“Because fatherhood is a duty and a responsibility but being a husband is a commitment. It’s harder to be a husband so I intentionally put in more daily. Here is my theory about living together as a husband and wife.”

I wrote in my Notes, BIG BANG ENGINEER THEORY.

“First, you don’t have to win every argument. Second. The rule, my rule at least, is always that the more dominant partner in the marriage has to give more than the less dominant partner. If your opinions are the loudest or strongest you have to sacrifice more for the marriage. And that person has to keep giving a bit of themselves every day to balance everything out.”

And lesson on money, Engineer?

“Spend ONLY on what you need, never what you want because you will never get enough of what you want. It’s a dark hole that keeps taking and taking.”

We drained our beverages and went to find his wife. She was in a corner working. She stood up. She was tall. A tall paediatrician and a teacher. She’s a professor at UoN. Professor Ruth Wanjiru. I could tell the Engineer was proud of her by the way he introduced her. How he looked at her. Like she was his secret weapon, his Ace card. Prof was gracious and said other nice things about him (I’m proud of him) and about me. “He talks very highly of you,” she said, “thanks for inspiring him to write.”

Engineer Nduati attended my writing masterclass in 2021. He’s the oldest male to attend my class. [The oldest female and most distinguished persona to attend is the Chief Justice Martha Koome who should have started writing her book but no pressure]. Engineer Nduati class was paid for by one of his daughters-in-law and his daughter, who felt like he had words in him, based on bristling emails he wrote to his daughter and to a common email group they have.

His book is called Gookaa From The Village To The City. It’s wild like Gooka’s hat. To show you what kind of a wacky Gooka engineer is, the book starts like this.

I was born in the city, like some of you. I survived the Mau Mau, unlike many of you. I grew up in the village, like some of you. I fought other boys, like many of you. I feared the girls, like many boys do. I slept hungry like many still do. School had good memories but sometimes a bore, or so I thought. Once I was young and full of life, like many you see. I never will grow old, said I to self. A grandfather was as archaic as my mind would say. From a baby to a boy to a father, from a father to a grandfather, a gooka. Gooka I am today, Gooka tomorrow you will be.

“Were you a great father?”

“I’m still a great father.” He said. “I think I have been a very good father.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I see how we relate and how other children relate with their parents. I’m very close with my children, but you can’t forge this closeness if you don’t put in the time. Time is the secret to great fatherhood. Time, time, time” he repeated. “That’s the most important thing children need from you. As a young engineer I deliberately made a decision not to go on sites away outside Nairobi when my colleagues were taking those jobs to make more money. This detached them from their children. Jobs do that. If you see them talking to their children now, you can’t believe that they are their children. There is a disconnect, because you made certain decisions that prioritised what you wanted over time with your children. Of course that gave them a better life at that time, a bigger car or house, but at the expense of their relationship with their children.”

Earlier in their marriage, his wife left for further studies abroad for nine months. “My children were very young. I would leave work and take lunch home every day. In the evening I would go straight home and cook and see them in bed.” Teenage was hard, but “you have to find a way to connect with them so I would go and shoot pool with my sons, so that they don’t feel deprived of something. My daughter has a 10 and 13 year gap with her brothers, so they raised her. They changed nappies and what not. This made them very close but also prepared them to be fathers themselves. And I think they are great fathers.”

His fatherhood mentality is greatly informed by a book he read before his children were born. “My wife is a paediatrician and she had this book in the house called The Common Sense Book of Baby and childcare by Benjamin Spock.” he leaned across the table,” nobody is born knowing what to do, you can’t do things right without reading and learning from others experiences.”

He met his wife in Canada in the late 1970s. He probably had a big afro and wide-ankled pants and writhed on the dancefloor in a disco. [Yeah, back in the day people went to the disco. The disco sounds hella serious] The city council had sponsored his education to the US, and this one time he went to Ottawa for the weekend to visit his boy called Muia Wachira. They were thick as thieves. It was summer. Muia used to run marathons in Ottawa, they both loved running, so on a Saturday they went running and then later they went to a dinner party thrown at the Kenyan embassy’s counsellor’s residence because Muia was that guy. Muia was the Kevo of their generation. He knew people and happening things. A guy of form.

Unbeknownst to him the party was in honour of this lady who was a medical student on an exchange program in Montreal, also visiting for the weekend. Her uncle was throwing the party or something. They met at this party. He must have seen her across the table, slim, elegant, saying something smart and he leaned in and whispered to Muia, “who’s that chic?”

“That’s Ciru. Ruth Wanjiru,” Muia said, his dessert spoon in his hand. “Why, you dig her?”

“Yeah, she fine.” He said.

The next day they all went to this thing he called The Trooping of The Colour event which I didn’t know about and didn’t want to interrupt the story by asking him, ‘waz that?” So I googled it later in my own free time so that you don’t have to. It’s a fanfare event to mark the birthday of the British sovereign. So,1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses, a jamboree of sorts, a spectacle. Engineer Nduati was the cameraman who took pictures and after the event, Ruth from the party told him, “make sure you send me those photos when we get back to Kenya.”

But Engineer was a bit slow. It took his boy Muia telling him, “boss, that chick asked about the photos.”

“Oh, I’m yet to process the film.”

“It’s not about the damn photos. She is asking about you. What are you doing?! Si you make your move.” So he patted his afro and said, OK, hold my beer. The rest is history. They are happily married now, 40 years in July.

“It wasn’t love at first sight. It developed organically over time.” he told me, “Sometimes love isn’t a big explosion. Sometimes it’s a small spark that causes a small fire and which grows and grows till it is big.”

“So, 40 years. So what’s the secret to a long happy marriage?”

“I have had a good marriage because I believe in what Kahil Gibran believes about marriage,” he said.

“What does Kahil Gibran believe about marriage?”

“That your wife doesn’t belong to you.” He said. “Gabrin believes that you and your wife are like two trees in a forest growing next to each other. One tree is protecting the other on one side from winds and storms while the other is doing the same from the other side. But they remain separate and rooted next to each other. Co-existing while being different.”

“I like that.” I said. “I really do.”

“Exactly. Your wife doesn’t belong to you!” he said. “You have to give ladies their space to be who they are.”

I wrote on my notes; give the tree space to be the tree she wants to be. Then I added under that sentence: Two trees. Forest. Different monkeys.

“But surely,” I said looking up from my childish literature, “you weren’t born knowing all these. You were married at 27, you must have fumbled a lot before you discovered these gems, yes?”

Yes, he said. Then he told me that his dad was polygamous. His mom was the first wife, which meant she wasn’t as favoured as the second wife. “You have to learn from every experience and I learnt from watching my father and his two wives. I learnt what not to do by watching what he was doing.”

“What does your wife complain about most concerning you?” I asked.

“That I don’t let her speak.”

“You are always talking.”

He laughed. “Yeah, she always says, please let me speak! That I don’t give her opinions as much thought as I should. But my wife is such a lovely lady, we have a good marriage. In fact, she dropped me off here, she is seated somewhere in this restaurant. Do you want to meet her?”

“I’d love to!” I shrieked. “By the way, what are you better at, being a dad or a husband?”

No sooner had the word husband left my lips than he said, “definitely a husband! I’m a better husband than I am a dad. You know why?”

“Why?”

“Because fatherhood is a duty and a responsibility but being a husband is a commitment. It’s harder to be a husband so I intentionally put in more daily. Here is my theory about living together as a husband and wife.”

I wrote in my Notes, BIG BANG ENGINEER THEORY.

“First, you don’t have to win every argument. Second. The rule, my rule at least, is always that the more dominant partner in the marriage has to give more than the less dominant partner. If your opinions are the loudest or strongest you have to sacrifice more for the marriage. And that person has to keep giving a bit of themselves every day to balance everything out.”

And lesson on money, Engineer?

“Spend ONLY on what you need, never what you want because you will never get enough of what you want. It’s a dark hole that keeps taking and taking.”

We drained our beverages and went to find his wife. She was in a corner working. She stood up. She was tall. A tall paediatrician and a teacher. She’s a professor at UoN. Professor Ruth Wanjiru. I could tell the Engineer was proud of her by the way he introduced her. How he looked at her. Like she was his secret weapon, his Ace card. Prof was gracious and said other nice things about him (I’m proud of him) and about me. “He talks very highly of you,” she said, “thanks for inspiring him to write.”

Engineer Nduati attended my writing masterclass in 2021. He’s the oldest male to attend my class. [The oldest female and most distinguished persona to attend is the Chief Justice Martha Koome who should have started writing her book but no pressure]. Engineer Nduati class was paid for by one of his daughters-in-law and his daughter, who felt like he had words in him, based on bristling emails he wrote to his daughter and to a common email group they have.

His book is called Gookaa From The Village To The City. It’s wild like Gooka’s hat. To show you what kind of a wacky Gooka engineer is, the book starts like this.

I was born in the city, like some of you. I survived the Mau Mau, unlike many of you. I grew up in the village, like some of you. I fought other boys, like many of you. I feared the girls, like many boys do. I slept hungry like many still do. School had good memories but sometimes a bore, or so I thought. Once I was young and full of life, like many you see. I never will grow old, said I to self. A grandfather was as archaic as my mind would say. From a baby to a boy to a father, from a father to a grandfather, a gooka. Gooka I am today, Gooka tomorrow you will be.

Then off he launches into 290 pages of Gooka talk. The back has a picture of him in 2021 looking grim. The next photo is him in 1967 standing next to signage of his high school, alma mater, Njiiri School, ironically named after chief Njiiri, a collaborator during the struggle. [He told me how Njiiri used to fly over the village in a government helicopter saying how there will never be independence]

“I am grandfather, I jog, have a limp, a missing molar, white hair and my eyesight,: he writes in the back sleeve of that book. “Look at my pictures again. In 1967 I was not smiling, like Fermat’s theorem in mathematics, which took 200 years to prove, can you decipher why I am not smiling in not more than five words, and email your answer to [email protected] The first 100 correct answers get a free autographed copy of the book. [Government taxes and postage on you.]

Ha-ha. Like I said, a wacky gooka.

He also has a children’s colouring book. [I bought this one, the other one was an ahsante]. Kim should be able to enjoy the stories in there which come with lessons. His book also has a Braille version which he showed me. He also has numerous bookmarks with numerous messages like ‘you miss 100% of the shots you do not take” and behind a road safety message.

Retirement for who? Gooka is busy shaking the bushes, at what 69? I’m particularly proud that he has accomplished what he said he would do during the writing masterclass; to write a book. I’m very impressed because writing a book can be a beautiful but daunting commitment.

**

The first writing masterclass this year is at the end of March. Register HERE.

Note: I give homework in those classes.

Then off he launches into 290 pages of Gooka talk. The back has a picture of him in 2021 looking grim. The next photo is him in 1967 standing next to signage of his high school, alma mater, Njiiri School, ironically named after chief Njiiri, a collaborator during the struggle. [He told me how Njiiri used to fly over the village in a government helicopter saying how there will never be independence]

“I am grandfather, I jog, have a limp, a missing molar, white hair and my eyesight,: he writes in the back sleeve of that book. “Look at my pictures again. In 1967 I was not smiling, like Fermat’s theorem in mathematics, which took 200 years to prove, can you decipher why I am not smiling in not more than five words, and email your answer to [email protected] The first 100 correct answers get a free autographed copy of the book. [Government taxes and postage on you.]

Ha-ha. Like I said, a wacky gooka.

He also has a children’s colouring book. [I bought this one, the other one was an ahsante]. Kim should be able to enjoy the stories in there which come with lessons. His book also has a Braille version which he showed me. He also has numerous bookmarks with numerous messages like ‘you miss 100% of the shots you do not take” and behind a road safety message.