She waited alone for her Uber outside the gate of one of the clustered grey-looking apartments in South B. It was past midnight and the street was forlorn and deserted. A stray mangy dog with old, grey fur stopped to raise its rear leg to piss by the roadside, unembarrassed that she was staring.

“Just like a man,” she thought to herself. The dog trotted off on its merry way, probably to find a bitch.

It had been raining and the street lights reflected off the wet tarmac, creating child-like abstract patterns. The app said her driver was three minutes away, coming through the back exit of Capital Center. His name was John. From his picture he looked like a smoker. Or someone who used to test the temperature of boiling kettle with his lips. Passing cars occasionally slowed down, but only briefly for the drivers to peer at the lone lady in the night before driving away because in Nairobi it’s probably a good idea to mind your own business at that hour. She was not scared of the night because her life seemed to be a twilight itself. She understood this moment perfectly, of standing alone, of waiting for worse things to happen to her. But don’t mistake this moment for bravery, because that would be to romanticise and oversimplify it, but even more tragically, that would be to mean the absence of fear. This was worse, this was despair.

The man she was from enjoying bednastics (my editor’s word, not mine) with was upstairs in his house, probably in the shower now lathering his hair, large suds gathering at his feet like snow. He could have walked her down and waited for the Uber with her but that would have been what a gentleman does (and he wasn’t) but she had also made it clear – through words and deeds – that she was not looking for a gentleman, that all she was looking was to get laid. Besides, she had made the decision to be a man – as a verb, at least. She wanted to operate the way she imagined men operated; removed, selfish, without any attachment to sex. She had come to his house for sex, gotten the sex and now she was going to grab her taxi and sit behind the driver while staring at the back of his head the whole way home.

We will be here until dawn if she starts dwelling on the stories of these late nights or dawn taxi rides home, like a soldier coming from a long senseless war; spent, empty, hopeless and haunted by their actions. At some point she could remember the men as individuals with names. This was when it would start with dates, these formalities over drinks and lunches, a musical chairs of the flesh, where she knew what she wanted and he knew what he wanted and they wanted the same thing but they wanted to give the impression of rising above their animalistic instincts and go through the motions of having teas and muffins as a precursor to sex.

She was always very clear what she wanted. She didn’t want a relationship. She didn’t want a ring. Or diseases. Or romantic trips to a beach where she would wear a nice dress and run an eyeliner around the ridges of her eyes and go for the buffet hotel dinner like a couple. No, not that kettle of fish. She didn’t want that shit. She wanted to get laid. Then leave. She didn’t care if they asked her if she had gotten home safely. If she came to your house it was because she didn’t want to have you over at hers. She went over at your house because she might have seen something in your that warned her that she couldn’t allow you in her space. It could be anything from how close your eyes were set together or how you asked the waitress for the bill in a way that she didn’t like. So, she came to yours because she could leave when she wanted and she never allowed you to call for her an Uber, because then you would know where she lived and that was the last thing she wanted. That and babies.

For a few years, her life was a blitz of men, a Rolodex of men. There was the man who always switched off all the lights to undress in darkness. The one who was cocky while in his clothes but but wept after sex. The buffed men who took time staring at themselves in the bedroom mirror. The men who started off saying this was about sex but after a while wanted to change the rules, got jealous, wanted to be in “something.” There were the silent mousy and frail looking men who suddenly had the strength of two men in the sack. The man who liked his toes sucked. The maniac bunnies who wouldn’t stop. The men who wanted to record themselves during sex, perhaps to watch in traffic. The vain and selfish men who thought it was about themselves. The kind ones, who were not cut out for that kind of sex, who she felt had found themselves in this dark neck of the woods. Those made her feel sorry for them when they looked lovingly into her eyes hoping to see something loving in her. The men who couldn’t get an erection and those who got one but couldn’t sustain one. The newly-divorced man from Naivasha Road who kept knickers of all the women he had slept with as mementos. It was his thing, like some men keep seminar lanyards. Or stamps. The man who wanted her to dress in fishnets and a hat and heels. The ones who gave her a lap dance because she loves it when a man lap dances for her as she sits there looking at them like sirloin. She never had many rules, but one that she never compromised was that she never slept with married men. The other was that she always picked the men – not the other way round – and she picked the men who were damaged or conflicted or unhappy, men who were having issues with their girlfriends, men who had just broken up with their girlfriends, men who were separated or were in boring relationships or in boring or sexless relationships. Basically men who were going through something in their lives and they wanted someone to distract them, to make them feel better about their moment. Men who mirrored her own turmoil.

At first these men had names – Charles, Ndegwa, Otieno, Patrick, Musau, Lawrence, Okello, Nyaboke, Kimani, Kiptanui – but then as the body count piled up, the Otienos and Wambuas started merging like a magic trick and finally they lost their names and they became just men.

“I was addicted to sex,” she says.

She had written me an email a day before my birthday, at 2:52am. I read it in bed on my birthday morning, which is how you want to start your birthday, reading about a woman with a sex addiction. She wrote it in two batches; the second one came at 3:28am. Most emails I have received at that hour have always been raw and vulnerable. The human soul haemorrhages, unbridled, at this hour. Late last year someone wrote me an email at 3am and said in conclusion, “Biko, give me one reason why I shouldn’t kill myself at right this moment.”

Of course I only read it in the morning after 9am (I know, very lazy of me; sleeping while I should be saving humanity) and I wrote back and said, “If you are still alive, you can’t kill yourself before you read The Goldfinch by Donna Tart. But if you are dead then your loss.” Turns out he was still alive. He went and read the book. (Took him a month!) Then he said, “I didn’t like it. So can I kill myself now?” I said, “No, hang on (he-he), try The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill.” Then he finished that and he loved it but then asked if there were lessons in these books he was missing and I told him that if you kill yourself you will not read such wonderful books out there. So now we occasionally recommend books to each other on email. I never asked why he wanted to kill himself. He never offered. But he’s still alive. Everybody wins.

When we met for breakfast – at Java Adams Arcade – I was surprised by two things; how voluptuous she was and how baby-ish her face was for her age. She was funny, self-deprecating and easy to talk to. It was cold, grey and drizzly outside the morning we met. We sat in a warm booth and blew our tea before sipping it, like Kales in Bomet. They played three popular songs from Elani’s album on a loop the whole time. It was fun at the beginning but then after two hours it started feeling like some sort of musical fundamentalism. Like Java was trying to indoctrinate us with Elani’s music so that we get to do Kookoo things. (Ha! See what I did there?).

She grew up in a big family in a middle-class neighbourhood marked by brick maisonettes, famous in the 90s for hot girls, flashy matatus and touts who were pop-culture gods. She doesn’t remember anything good about her childhood even though they never lacked for anything. She remembers relatives who lived with them, a revolving door of them. It felt crowded.

“I grew up with many siblings and I felt lost in the family crowd. Nobody noticed me,” she now says. “It didn’t help that my dad from the beginning picked his favourite child – my big sister – and didn’t seem to mind if it would hurt the rest of us how he showed that he loved her more than he loved me. I always felt that I had to be like her to get my father’s love. She is named after his mom and I’m named after my mom’s mom. Maybe for that reason, he doted on my big sister. I remember how I would fight with my sister and he would always take her side, even make me apologise to her when she was on the wrong. I resented her. This went on even into adulthood, when he would use her as a yardstick – he would ask me why I couldn’t be like her. I grew up feeling unloved, unchosen.

“I remember many things about my relationship with my father but one of the things I recall clearly is how one day I rode with him in his car, just the two of us, for an hour and we never exchanged one word. We never had anything to tell each other. For a long time I suspected that he wasn’t my real father until I saw my birth certificate and confirmed that he was indeed my father. It was confusing to me why he would love me less than my sister. I wasn’t like her, I couldn’t be like her but he wanted me to be like her and measured me against her.”

She also remembers his constant drinking, her parents’ fights, waking up to find that he had spent the night on the couch, still in his socks, his loud drunken snores filling the living room. She remembers car crashes whilst he was under the influence, him falling into ditches, him being arrested by cops while drunk, him being found slumped in the car, passed out from booze, her mother going to bed at night and telling them “your father’s food is there, serve him whenever he comes home.”

“I just had a bad childhood, feeling unloved by him.”

“Did you like him?”

“Like him?”

“Yeah. You might have loved him as a father, but did you like him as a person?”

“Wow.” She leans back on her chair to contemplate this question. “I have never thought of it that way.” The void caused by the pause is filled by Wambui’s voice in the song Milele.

“I didn’t like him.” She says finally.

The little self esteem she had left from her relationship with her father was obliterated by her mother. “My mother, as far back as when I was a child, and even as recently as two years ago, would make hurtful comments about my body. She would say ‘You are too short, your butt is too big, your hips are too wide, you are too fat.’ In my whole life, I don’t remember when she didn’t body shame me. When I turned 12, my hips just grew wide and she would make comments about them and constantly admonish me if she saw me eating. She even had a name for me, she called me Ngatinku, which is Meru for tree stump.”

I hand her my phone to spell it for me because Meru words sound like termites crawling down your nose making you want to sneeze but you can’t because you have food in your mouth. Ngatinku, doesn’t it feel like a word that comes from the very back of your nose?

“So, here you had, on the one hand, a father who constantly compared me with my sis and on the other I had a mother who constantly shamed my body. So I grew up with mad body issues and no self-esteem. There is low self-esteem where you at least think you are good for something or good at something then there is no self esteem where you feel worthless. That was my whole childhood.”

She got her period early, at 10-years, way before other girls, which further threw a spanner in the works. Her life became a big bag of confusion, confronted by many intense feelings of neglect, betrayal, hatred and rejection. In school she barely spoke, barely participated in class and her grades plummeted with her self esteem. She was the lone child at break, keeping to herself at a corner, wondering why she was different, why she couldn’t fit in, why she couldn’t be loved, why she deserved the cards she had been dealt, why her and not that nasty girl from Class 5 Flamingo? She was a good person. She didn’t deserve this.

At 14-years she had had it. She locked herself in the room one afternoon and tried committing suicide. She slashed her wrists with a sharp razor. “I wanted to die without hurting myself. I wanted to die but I was afraid of the pain that comes with dying. I hated my body, this body my mother had told me was wide at the hips and big on the behind. I wanted to inflict this physical pain to match the pain I felt emotionally. I wanted to destroy it. I wanted to destroy myself so that the world would be free of my presence.”

She didn’t die, of course when her parents saw the cuts, there was a half-assed attempt to counsel her but “generally nobody bothered.”

Because she felt useless she scored 320/ 500 in KCPE and her parents were greatly disappointed. She felt like an embarrassment to the family because her sister had gone to a better high school. They found a school for her in the middle of Kajiado. That school was like the end of the world. First it was dry, nothing seemed to grow there. Second it was so windy clothes would dry in under an hour. The sky was so blue but barely inspiring. If you stood and looked around, there was nothing to see for kilometers, just nothingness marked by short shrubs, rocks, rising waves of heat and dust, right up to the point where the bright blue cloudless sky finally met the earth.

“I felt abandoned, like they had gotten rid of me.”

High school was a nightmare. She didn’t fit in. There were two groups; the city girls and the Maasai girls from the neighbouring villages. The city girls hated her because she came from a fairly better off family than them. The village girls couldn’t accept her because she was from the city and city girls were stuffy and snobbish and all they wanted to talk about was someone called Ne-Yo. So she was alone once again. “I never want to see 80% of people from high school because they made my life pure hell. They wouldn’t want to be with me. They gossiped about me, making up stories, for example that I was a lesbian.”

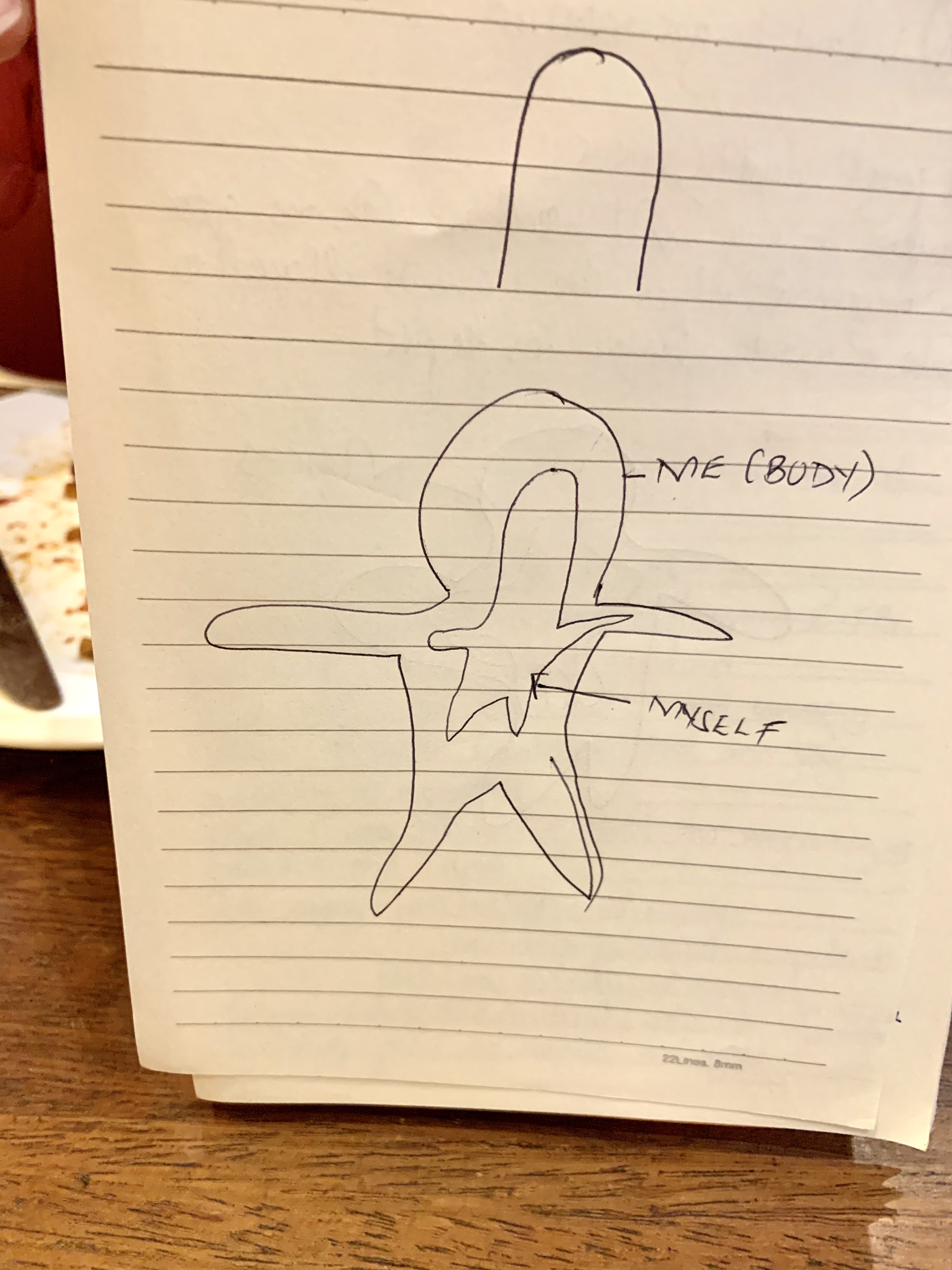

“Let me draw for you what I felt,” she says and rummages through her bag to retrieve an old notebook and a pen. “Don’t you have a notebook and a pen, Biko, like a proper writer?”

“I would have,” I say. “Only it’s 2019 and we have this thing called Notes on our phones.”

She raises her hands in mock surrender then opens a fresh page on her notebook and starts scribbling. There are two types of people who draw. The first type draws with their tongues stuck at the corner of their mouth, as if one bad stroke and our world implodes. The second type, draws with the same face they used while trying to thread a needle. She has neither. What she is, is a terrible artist. Some people can’t draw. Others can’t whistle. The really unfortunate can’t do either.

“What is that?” I ask her.

“This is me,” she says looking up, with a look like it’s obvious to anybody that what she’s drawing is a human being. It looks, to me, like a crown of a tooth. A bad tooth. A tooth that once loved sugar and ignored warnings that sugar was bad yet it felt it knew better than everybody else and so it continued having sugar until it got a cavity. She continues to draw this caricature.

“Are those supposed to be your arms?” I ask chuckling.

“Yes.” Her head is bent, undeterred.

“One of your hands is shorter,” I note helpfully about the drawing, which she chooses to ignore. Artists are touchy. Let me show you what she drew. Tell me if it doesn’t look like a bad tooth.

“You see this outer shell, this is my body,” she explains. “But I always felt like I was trapped in this body that I was told wasn’t good enough, a body that I didn’t like. The real me was inside this body, this one right here.” She points at the smaller tooth in the big tooth. The picture, to be honest, looks like a big tooth who walked around, met a small tooth and lured it with sweets and then ate it. But if she insists that’s her, who are we to go against the artist?

“I know this sounds like something a mzungu would say,” she continues. “But I really felt like if I removed my body, if I came out of my body, this outer body that nobody liked, I would release the inner me who everybody would then like. I really admired a girl in my high school called Jean. I wanted to be like her. She was bold and she never took any nonsense from anybody. She didn’t care if you liked her or not. That’s who I felt I was inside. Outside I was a doormat, someone who couldn’t defend herself from the school bullies, from my parents and from society. People just walked all over me. Of course I tried being like Jean by not giving a shit and that was a problem for people and when I gave a shit that was also a problem.”

Suffice it to say she didn’t score enough points to join the university and she had big fights with her parents who were, again, disappointed in her.

“My mom had a way of loving you and hating you at the same time and it was very confusing,” she says. “She also seemed to want me to be like my sister. She told me that with a C-plain I would only sell tomatoes for a living and I believed everything she told me. I didn’t grow up being affirmed by anyone. I grew up being told negative things and when that comes from your mother and father, you believe it.”

She joined a private university and there she met Johnny. I don’t want you to raise your hopes and think that finally Johnny is the one who will rescue her. Johnny was an asshole. But a handsome and charming asshole. He was bronzed and broad shouldered and when he walked his feet barely touched the ground, like Ekwueme, son of Adaku and Wigwe in The Concubine. Girls kissed his ring in uni. He would swagger around campus beating girls off him with a wooden girl-swatter. He had the eyes of the most gorgeous girls, taking his pick from that sorority like an entitled emperor. Johnny, a trapper like Ekwueme, finally ensnares our protagonist into his web. She is confused. Her? Johnny? What did he see in her?

He saw her hips and ample bottom. He saw everything her mother had convinced her was big and bad and fat and he told her that she was fresh, that she could “gerrit”. He saw her physical beauty, because she is beautiful, and that took her aback because nobody had ever thought of her as beautiful and here was Johnny with his full Maxwell lips, blowing her kisses and making her giggle. For the first time she was taken on a proper date by a man, Johnny himself, the son of Adaku and Wigwe, to eat fries and chicken and drink soda at KFC because KFC at that time was all the rage and guys were actually lining up for it like it was manna. She fell for him then Johnny tapped it, as the university students say and if you are reading this from June of 1985, “tap it” is not a Morse code, it’s to have “sexual intercourse” with a woman. They were barely an item before Johnny said, “This isn’t working. I don’t want this anymore.”

The bottom fell off and she fell into a deep, dark pit.

“I had flirted with the idea that perhaps someone could love me when Johnny and I started dating but when he left me, I was sure that I didn’t deserve to be loved. That my parents had been right all along. What was I thinking, that I deserved love? My self hatred deepened to another level.”

For over a month she was dazed, walking barefoot on the sharp shards of her broken heart. She felt like she was bleeding on the inside. The pain in her heart was physical. She thought of suicide a few times. She wouldn’t eat or sleep. She would stay awake the whole night, staring at a lit candle burn out till darkness engulfed the whole room. “I still stare at burning candles. It’s my therapy.”

Meanwhile Johnny went about living his life as usual, a new bird hanging on his arm. She would see him in the cafeteria, making a knot of girls crumble in giggles. Or walking across the lawn, carrying his books in one hand, the sun in his face, a girl on the other hand. Good old Johnny going about his life without a f*ckn bruise. She looked at him and thought, how can this bastard move on like nothing happened, like a big love train just didn’t get off the rails here? How can he even breathe in the wreckage of my heart?

“This is when I made a decision in my life. That I would never have sex because of love. Or love because of sex. I’d never show my heart. That I’d operate like a man.”

“And just like that my whoring days started.”

And they continued right after university; she felled men like logs and left them lying there to rot in the soil. If you dared show or told her that you liked her, she would cut you loose. She also started drinking at some point, drinking heavily, and since she’s a lightweight, her drinking was three guaranas, maybe some vodkas, always in her house and only over the weekend.

“I didn’t know it then, but I was escaping,” she says. “I hated myself. I saw girls my age date decent guys while I was just jumping from one guy to the next. I was addicted to sex the way some people are addicted to alcohol or gambling. I wanted sex to numb the pain. A guy saying no was a challenge. It was easier to get naked for a guy than fall in love. Love became a metaphor, a fairy tale for other people. But with sex also came lunatics. I have seen all types of psychotic men in this town.”

She sips her coffee and collects her thoughts.

“Biko, I was dying inside and having sex and drinking was my way of trying to find solutions. I even tried counselling. It didn’t work. I was getting sicker and sicker. I would pray to God to help me get through the day without thinking about sex. At some point I tried to stab myself in the stomach with a knife to end it all. I held the knife to my stomach and started crying because I was weak and too cowardly. I remember going to see a pastor for counselling and he told me that I was just a horny girl and that my parents thought I was a loser. Can you believe it?” She laughs dryly. “In some ways I thought that if this pastor can say such things to me, then he also must be right. I was a sexual misfit.”

“So the biggest problem was not alcohol but sex?” I ask.

“Yeah. There were days I would be in the office and I would start trembling from being horny. I would be at my desk at 11am and my whole body would start shaking and I’d be so horny I’d not be able to think or do anything. I’d close my thighs tight and control my breathing. I’d walk around to let it pass and if it didn’t I’d start chatting up one of the men I was shagging and arrange for a meet up.”

“What if he was said he was busy?” I ask. (Like he has to take his cat to the cat dentist.)

“Then I’d hit up the next guy. I had guys lined up; if one said no, I’d holler at the next one. If he said he’s out of town, I’d go for guy C and D and so on,” she says. “I was having gruesome sex by this point, I liked to be shagged hard, to be roughed up, to be choked and my hair pulled against my scalp. Gruesome sex isn’t sex that you have to fulfill you. It’s empty. It’s the kind that ends up hurting you at the end of it. You end up not feeling good. I was punishing myself for being the way I was. I wanted to feel the pain for being who I was. At some point sex stopped having any effect on me. I tried to cover my pain, hatred, worthlessness and rejection with nice clothes and perfume but these things couldn’t fix me.”

It was like taking soda water.

“What’s your body count?” I ask her.

“I can’t tell you.” She sighs and looks away for the first time.

“Why not?”

Pause.

“Because I’m ashamed,” she says in a small voice.

She says it in a way that makes me want to hold her hand and tell her it doesn’t define her. She says it in a way that makes her vulnerable and little again, like that lonely, friendless girl in the school yard that nobody wanted to talk to. Those words, “because I’m ashamed,” make her brittle and innocent and it turns her heart into a small baby dove that hasn’t learnt about gravity.

On her 27th birthday she and a bunch of her drinking friends went to Westlands to celebrate. She promised herself that she wasn’t going to step into 28years living that life, it had aged her from the inside out. It was like she was carrying stones in her bones. She was going to have the last drink, the last sex.

She got a good lady pastor who was also a therapist. “She advised me to do an Esther’s fast, which is three days of fasting no water or food.” So she took some leave days and stayed in the house in her deera, curtains drawn, everything that emits sound switched off, just fasting and praying. “I prayed for God to take away my sexual urge. Sex was destroying me. It was a tool I was using to hurt myself.”

Somehow after the fast and prayers her urges reduced considerably. She stopped drinking. She deleted all the numbers she had of men she would sleep with. She lost almost all her friends who got swept away in this wave of change. She also lost her job and moved back home. The trembling stopped. She “backslid” twice, yes, but it wasn’t the same as before her fast. She found Jesus, afresh, got saved.

“It isn’t easy. I was in therapy every week with my pastor. I had to confront shit I’d avoided. It came to the surface. Lemme tell you when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it. Though I was going through a hard time, I found love in Christ. My parents attitude towards me has changed. They seem more appreciative and accommodating of me.”

We wait as the waitress clears the table.

“I have been going through a hard year and a half,” she continues. “Financially I wasn’t doing well but spiritually I was growing daily. My ability to overcome temptations was growing stronger. I began to believe in God and eventually I began to believe in myself. He fixed my esteem.”

To meet new people she joined Tinder one day in a moment of boredom. One day she matched with a guy whose profile picture was of Jesus on a cross. They started chatting. She liked his commitment to his faith. He also said he was abstaining. He asked her out four times before she agreed. “On our first date he came and picked me up and we went for a long drive around the southern bypass at night.”

“Wait. So you got into a car with a guy you met on Tinder, a guy with a picture of Jesus on a cross, and you went for a long drive at night alone with him?”

She laughs.

“Yeah.”

“You must have immense faith in humanity.”

“Well,” she says. “I forgot to mention that I had turned down four dates with him. But it turned out that he’s a really nice guy, and he proposed to me some time back.” She raises her finger. There is a glittering ring.

“You are getting married.”

“I didn’t think I wanted to, but he is really nice and he’s the only person who has never given up on me. He’s so patient with me. So, this is a promise, engagement ring. He says he will buy me a proper ring.”

“Looking back and knowing what you know now, what would you tell your 19-year old self?”

“I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”

“Most of your problems come from your childhood, from your mom and dad. Do you think you have to resolve this to move forward?” I ask.

“A few months ago, my dad told me he loves me,” she says. “I’d gone home to visit them and we were having dinner and he just told me, ‘I love you very much.’ He said it like ten times. I almost broke down and cried in front of him but I ran to my room – yes, I still have a room at home, it’s more like a store now – and I cried. I got on my knees and thanked God. That was a very healing moment. My mom always reminds me now that she loves me. She calls me daily just to find out how I’m doing. She is no longer judgy. She is really psyched about me settling down. I can say honestly that my relationship with God has significantly improved because of my folks.”

“Have you told your fiancé about your wild days?”

“Are you serious?” she asks, laughing. “I told him about two guys and going by his reaction I don’t think I want to find out his reaction if I told all. I mean, would you want to know?”

“No,” I say. “Look, I hope you have a fulfilling marriage.”

“Thanks.”

“You see this outer shell, this is my body,” she explains. “But I always felt like I was trapped in this body that I was told wasn’t good enough, a body that I didn’t like. The real me was inside this body, this one right here.” She points at the smaller tooth in the big tooth. The picture, to be honest, looks like a big tooth who walked around, met a small tooth and lured it with sweets and then ate it. But if she insists that’s her, who are we to go against the artist?

“I know this sounds like something a mzungu would say,” she continues. “But I really felt like if I removed my body, if I came out of my body, this outer body that nobody liked, I would release the inner me who everybody would then like. I really admired a girl in my high school called Jean. I wanted to be like her. She was bold and she never took any nonsense from anybody. She didn’t care if you liked her or not. That’s who I felt I was inside. Outside I was a doormat, someone who couldn’t defend herself from the school bullies, from my parents and from society. People just walked all over me. Of course I tried being like Jean by not giving a shit and that was a problem for people and when I gave a shit that was also a problem.”

Suffice it to say she didn’t score enough points to join the university and she had big fights with her parents who were, again, disappointed in her.

“My mom had a way of loving you and hating you at the same time and it was very confusing,” she says. “She also seemed to want me to be like my sister. She told me that with a C-plain I would only sell tomatoes for a living and I believed everything she told me. I didn’t grow up being affirmed by anyone. I grew up being told negative things and when that comes from your mother and father, you believe it.”

She joined a private university and there she met Johnny. I don’t want you to raise your hopes and think that finally Johnny is the one who will rescue her. Johnny was an asshole. But a handsome and charming asshole. He was bronzed and broad shouldered and when he walked his feet barely touched the ground, like Ekwueme, son of Adaku and Wigwe in The Concubine. Girls kissed his ring in uni. He would swagger around campus beating girls off him with a wooden girl-swatter. He had the eyes of the most gorgeous girls, taking his pick from that sorority like an entitled emperor. Johnny, a trapper like Ekwueme, finally ensnares our protagonist into his web. She is confused. Her? Johnny? What did he see in her?

He saw her hips and ample bottom. He saw everything her mother had convinced her was big and bad and fat and he told her that she was fresh, that she could “gerrit”. He saw her physical beauty, because she is beautiful, and that took her aback because nobody had ever thought of her as beautiful and here was Johnny with his full Maxwell lips, blowing her kisses and making her giggle. For the first time she was taken on a proper date by a man, Johnny himself, the son of Adaku and Wigwe, to eat fries and chicken and drink soda at KFC because KFC at that time was all the rage and guys were actually lining up for it like it was manna. She fell for him then Johnny tapped it, as the university students say and if you are reading this from June of 1985, “tap it” is not a Morse code, it’s to have “sexual intercourse” with a woman. They were barely an item before Johnny said, “This isn’t working. I don’t want this anymore.”

The bottom fell off and she fell into a deep, dark pit.

“I had flirted with the idea that perhaps someone could love me when Johnny and I started dating but when he left me, I was sure that I didn’t deserve to be loved. That my parents had been right all along. What was I thinking, that I deserved love? My self hatred deepened to another level.”

For over a month she was dazed, walking barefoot on the sharp shards of her broken heart. She felt like she was bleeding on the inside. The pain in her heart was physical. She thought of suicide a few times. She wouldn’t eat or sleep. She would stay awake the whole night, staring at a lit candle burn out till darkness engulfed the whole room. “I still stare at burning candles. It’s my therapy.”

Meanwhile Johnny went about living his life as usual, a new bird hanging on his arm. She would see him in the cafeteria, making a knot of girls crumble in giggles. Or walking across the lawn, carrying his books in one hand, the sun in his face, a girl on the other hand. Good old Johnny going about his life without a f*ckn bruise. She looked at him and thought, how can this bastard move on like nothing happened, like a big love train just didn’t get off the rails here? How can he even breathe in the wreckage of my heart?

“This is when I made a decision in my life. That I would never have sex because of love. Or love because of sex. I’d never show my heart. That I’d operate like a man.”

“And just like that my whoring days started.”

And they continued right after university; she felled men like logs and left them lying there to rot in the soil. If you dared show or told her that you liked her, she would cut you loose. She also started drinking at some point, drinking heavily, and since she’s a lightweight, her drinking was three guaranas, maybe some vodkas, always in her house and only over the weekend.

“I didn’t know it then, but I was escaping,” she says. “I hated myself. I saw girls my age date decent guys while I was just jumping from one guy to the next. I was addicted to sex the way some people are addicted to alcohol or gambling. I wanted sex to numb the pain. A guy saying no was a challenge. It was easier to get naked for a guy than fall in love. Love became a metaphor, a fairy tale for other people. But with sex also came lunatics. I have seen all types of psychotic men in this town.”

She sips her coffee and collects her thoughts.

“Biko, I was dying inside and having sex and drinking was my way of trying to find solutions. I even tried counselling. It didn’t work. I was getting sicker and sicker. I would pray to God to help me get through the day without thinking about sex. At some point I tried to stab myself in the stomach with a knife to end it all. I held the knife to my stomach and started crying because I was weak and too cowardly. I remember going to see a pastor for counselling and he told me that I was just a horny girl and that my parents thought I was a loser. Can you believe it?” She laughs dryly. “In some ways I thought that if this pastor can say such things to me, then he also must be right. I was a sexual misfit.”

“So the biggest problem was not alcohol but sex?” I ask.

“Yeah. There were days I would be in the office and I would start trembling from being horny. I would be at my desk at 11am and my whole body would start shaking and I’d be so horny I’d not be able to think or do anything. I’d close my thighs tight and control my breathing. I’d walk around to let it pass and if it didn’t I’d start chatting up one of the men I was shagging and arrange for a meet up.”

“What if he was said he was busy?” I ask. (Like he has to take his cat to the cat dentist.)

“Then I’d hit up the next guy. I had guys lined up; if one said no, I’d holler at the next one. If he said he’s out of town, I’d go for guy C and D and so on,” she says. “I was having gruesome sex by this point, I liked to be shagged hard, to be roughed up, to be choked and my hair pulled against my scalp. Gruesome sex isn’t sex that you have to fulfill you. It’s empty. It’s the kind that ends up hurting you at the end of it. You end up not feeling good. I was punishing myself for being the way I was. I wanted to feel the pain for being who I was. At some point sex stopped having any effect on me. I tried to cover my pain, hatred, worthlessness and rejection with nice clothes and perfume but these things couldn’t fix me.”

It was like taking soda water.

“What’s your body count?” I ask her.

“I can’t tell you.” She sighs and looks away for the first time.

“Why not?”

Pause.

“Because I’m ashamed,” she says in a small voice.

She says it in a way that makes me want to hold her hand and tell her it doesn’t define her. She says it in a way that makes her vulnerable and little again, like that lonely, friendless girl in the school yard that nobody wanted to talk to. Those words, “because I’m ashamed,” make her brittle and innocent and it turns her heart into a small baby dove that hasn’t learnt about gravity.

On her 27th birthday she and a bunch of her drinking friends went to Westlands to celebrate. She promised herself that she wasn’t going to step into 28years living that life, it had aged her from the inside out. It was like she was carrying stones in her bones. She was going to have the last drink, the last sex.

She got a good lady pastor who was also a therapist. “She advised me to do an Esther’s fast, which is three days of fasting no water or food.” So she took some leave days and stayed in the house in her deera, curtains drawn, everything that emits sound switched off, just fasting and praying. “I prayed for God to take away my sexual urge. Sex was destroying me. It was a tool I was using to hurt myself.”

Somehow after the fast and prayers her urges reduced considerably. She stopped drinking. She deleted all the numbers she had of men she would sleep with. She lost almost all her friends who got swept away in this wave of change. She also lost her job and moved back home. The trembling stopped. She “backslid” twice, yes, but it wasn’t the same as before her fast. She found Jesus, afresh, got saved.

“It isn’t easy. I was in therapy every week with my pastor. I had to confront shit I’d avoided. It came to the surface. Lemme tell you when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it. Though I was going through a hard time, I found love in Christ. My parents attitude towards me has changed. They seem more appreciative and accommodating of me.”

We wait as the waitress clears the table.

“I have been going through a hard year and a half,” she continues. “Financially I wasn’t doing well but spiritually I was growing daily. My ability to overcome temptations was growing stronger. I began to believe in God and eventually I began to believe in myself. He fixed my esteem.”

To meet new people she joined Tinder one day in a moment of boredom. One day she matched with a guy whose profile picture was of Jesus on a cross. They started chatting. She liked his commitment to his faith. He also said he was abstaining. He asked her out four times before she agreed. “On our first date he came and picked me up and we went for a long drive around the southern bypass at night.”

“Wait. So you got into a car with a guy you met on Tinder, a guy with a picture of Jesus on a cross, and you went for a long drive at night alone with him?”

She laughs.

“Yeah.”

“You must have immense faith in humanity.”

“Well,” she says. “I forgot to mention that I had turned down four dates with him. But it turned out that he’s a really nice guy, and he proposed to me some time back.” She raises her finger. There is a glittering ring.

“You are getting married.”

“I didn’t think I wanted to, but he is really nice and he’s the only person who has never given up on me. He’s so patient with me. So, this is a promise, engagement ring. He says he will buy me a proper ring.”

“Looking back and knowing what you know now, what would you tell your 19-year old self?”

“I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”

“Most of your problems come from your childhood, from your mom and dad. Do you think you have to resolve this to move forward?” I ask.

“A few months ago, my dad told me he loves me,” she says. “I’d gone home to visit them and we were having dinner and he just told me, ‘I love you very much.’ He said it like ten times. I almost broke down and cried in front of him but I ran to my room – yes, I still have a room at home, it’s more like a store now – and I cried. I got on my knees and thanked God. That was a very healing moment. My mom always reminds me now that she loves me. She calls me daily just to find out how I’m doing. She is no longer judgy. She is really psyched about me settling down. I can say honestly that my relationship with God has significantly improved because of my folks.”

“Have you told your fiancé about your wild days?”

“Are you serious?” she asks, laughing. “I told him about two guys and going by his reaction I don’t think I want to find out his reaction if I told all. I mean, would you want to know?”

“No,” I say. “Look, I hope you have a fulfilling marriage.”

“Thanks.”

“You see this outer shell, this is my body,” she explains. “But I always felt like I was trapped in this body that I was told wasn’t good enough, a body that I didn’t like. The real me was inside this body, this one right here.” She points at the smaller tooth in the big tooth. The picture, to be honest, looks like a big tooth who walked around, met a small tooth and lured it with sweets and then ate it. But if she insists that’s her, who are we to go against the artist?

“I know this sounds like something a mzungu would say,” she continues. “But I really felt like if I removed my body, if I came out of my body, this outer body that nobody liked, I would release the inner me who everybody would then like. I really admired a girl in my high school called Jean. I wanted to be like her. She was bold and she never took any nonsense from anybody. She didn’t care if you liked her or not. That’s who I felt I was inside. Outside I was a doormat, someone who couldn’t defend herself from the school bullies, from my parents and from society. People just walked all over me. Of course I tried being like Jean by not giving a shit and that was a problem for people and when I gave a shit that was also a problem.”

Suffice it to say she didn’t score enough points to join the university and she had big fights with her parents who were, again, disappointed in her.

“My mom had a way of loving you and hating you at the same time and it was very confusing,” she says. “She also seemed to want me to be like my sister. She told me that with a C-plain I would only sell tomatoes for a living and I believed everything she told me. I didn’t grow up being affirmed by anyone. I grew up being told negative things and when that comes from your mother and father, you believe it.”

She joined a private university and there she met Johnny. I don’t want you to raise your hopes and think that finally Johnny is the one who will rescue her. Johnny was an asshole. But a handsome and charming asshole. He was bronzed and broad shouldered and when he walked his feet barely touched the ground, like Ekwueme, son of Adaku and Wigwe in The Concubine. Girls kissed his ring in uni. He would swagger around campus beating girls off him with a wooden girl-swatter. He had the eyes of the most gorgeous girls, taking his pick from that sorority like an entitled emperor. Johnny, a trapper like Ekwueme, finally ensnares our protagonist into his web. She is confused. Her? Johnny? What did he see in her?

He saw her hips and ample bottom. He saw everything her mother had convinced her was big and bad and fat and he told her that she was fresh, that she could “gerrit”. He saw her physical beauty, because she is beautiful, and that took her aback because nobody had ever thought of her as beautiful and here was Johnny with his full Maxwell lips, blowing her kisses and making her giggle. For the first time she was taken on a proper date by a man, Johnny himself, the son of Adaku and Wigwe, to eat fries and chicken and drink soda at KFC because KFC at that time was all the rage and guys were actually lining up for it like it was manna. She fell for him then Johnny tapped it, as the university students say and if you are reading this from June of 1985, “tap it” is not a Morse code, it’s to have “sexual intercourse” with a woman. They were barely an item before Johnny said, “This isn’t working. I don’t want this anymore.”

The bottom fell off and she fell into a deep, dark pit.

“I had flirted with the idea that perhaps someone could love me when Johnny and I started dating but when he left me, I was sure that I didn’t deserve to be loved. That my parents had been right all along. What was I thinking, that I deserved love? My self hatred deepened to another level.”

For over a month she was dazed, walking barefoot on the sharp shards of her broken heart. She felt like she was bleeding on the inside. The pain in her heart was physical. She thought of suicide a few times. She wouldn’t eat or sleep. She would stay awake the whole night, staring at a lit candle burn out till darkness engulfed the whole room. “I still stare at burning candles. It’s my therapy.”

Meanwhile Johnny went about living his life as usual, a new bird hanging on his arm. She would see him in the cafeteria, making a knot of girls crumble in giggles. Or walking across the lawn, carrying his books in one hand, the sun in his face, a girl on the other hand. Good old Johnny going about his life without a f*ckn bruise. She looked at him and thought, how can this bastard move on like nothing happened, like a big love train just didn’t get off the rails here? How can he even breathe in the wreckage of my heart?

“This is when I made a decision in my life. That I would never have sex because of love. Or love because of sex. I’d never show my heart. That I’d operate like a man.”

“And just like that my whoring days started.”

And they continued right after university; she felled men like logs and left them lying there to rot in the soil. If you dared show or told her that you liked her, she would cut you loose. She also started drinking at some point, drinking heavily, and since she’s a lightweight, her drinking was three guaranas, maybe some vodkas, always in her house and only over the weekend.

“I didn’t know it then, but I was escaping,” she says. “I hated myself. I saw girls my age date decent guys while I was just jumping from one guy to the next. I was addicted to sex the way some people are addicted to alcohol or gambling. I wanted sex to numb the pain. A guy saying no was a challenge. It was easier to get naked for a guy than fall in love. Love became a metaphor, a fairy tale for other people. But with sex also came lunatics. I have seen all types of psychotic men in this town.”

She sips her coffee and collects her thoughts.

“Biko, I was dying inside and having sex and drinking was my way of trying to find solutions. I even tried counselling. It didn’t work. I was getting sicker and sicker. I would pray to God to help me get through the day without thinking about sex. At some point I tried to stab myself in the stomach with a knife to end it all. I held the knife to my stomach and started crying because I was weak and too cowardly. I remember going to see a pastor for counselling and he told me that I was just a horny girl and that my parents thought I was a loser. Can you believe it?” She laughs dryly. “In some ways I thought that if this pastor can say such things to me, then he also must be right. I was a sexual misfit.”

“So the biggest problem was not alcohol but sex?” I ask.

“Yeah. There were days I would be in the office and I would start trembling from being horny. I would be at my desk at 11am and my whole body would start shaking and I’d be so horny I’d not be able to think or do anything. I’d close my thighs tight and control my breathing. I’d walk around to let it pass and if it didn’t I’d start chatting up one of the men I was shagging and arrange for a meet up.”

“What if he was said he was busy?” I ask. (Like he has to take his cat to the cat dentist.)

“Then I’d hit up the next guy. I had guys lined up; if one said no, I’d holler at the next one. If he said he’s out of town, I’d go for guy C and D and so on,” she says. “I was having gruesome sex by this point, I liked to be shagged hard, to be roughed up, to be choked and my hair pulled against my scalp. Gruesome sex isn’t sex that you have to fulfill you. It’s empty. It’s the kind that ends up hurting you at the end of it. You end up not feeling good. I was punishing myself for being the way I was. I wanted to feel the pain for being who I was. At some point sex stopped having any effect on me. I tried to cover my pain, hatred, worthlessness and rejection with nice clothes and perfume but these things couldn’t fix me.”

It was like taking soda water.

“What’s your body count?” I ask her.

“I can’t tell you.” She sighs and looks away for the first time.

“Why not?”

Pause.

“Because I’m ashamed,” she says in a small voice.

She says it in a way that makes me want to hold her hand and tell her it doesn’t define her. She says it in a way that makes her vulnerable and little again, like that lonely, friendless girl in the school yard that nobody wanted to talk to. Those words, “because I’m ashamed,” make her brittle and innocent and it turns her heart into a small baby dove that hasn’t learnt about gravity.

On her 27th birthday she and a bunch of her drinking friends went to Westlands to celebrate. She promised herself that she wasn’t going to step into 28years living that life, it had aged her from the inside out. It was like she was carrying stones in her bones. She was going to have the last drink, the last sex.

She got a good lady pastor who was also a therapist. “She advised me to do an Esther’s fast, which is three days of fasting no water or food.” So she took some leave days and stayed in the house in her deera, curtains drawn, everything that emits sound switched off, just fasting and praying. “I prayed for God to take away my sexual urge. Sex was destroying me. It was a tool I was using to hurt myself.”

Somehow after the fast and prayers her urges reduced considerably. She stopped drinking. She deleted all the numbers she had of men she would sleep with. She lost almost all her friends who got swept away in this wave of change. She also lost her job and moved back home. The trembling stopped. She “backslid” twice, yes, but it wasn’t the same as before her fast. She found Jesus, afresh, got saved.

“It isn’t easy. I was in therapy every week with my pastor. I had to confront shit I’d avoided. It came to the surface. Lemme tell you when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it. Though I was going through a hard time, I found love in Christ. My parents attitude towards me has changed. They seem more appreciative and accommodating of me.”

We wait as the waitress clears the table.

“I have been going through a hard year and a half,” she continues. “Financially I wasn’t doing well but spiritually I was growing daily. My ability to overcome temptations was growing stronger. I began to believe in God and eventually I began to believe in myself. He fixed my esteem.”

To meet new people she joined Tinder one day in a moment of boredom. One day she matched with a guy whose profile picture was of Jesus on a cross. They started chatting. She liked his commitment to his faith. He also said he was abstaining. He asked her out four times before she agreed. “On our first date he came and picked me up and we went for a long drive around the southern bypass at night.”

“Wait. So you got into a car with a guy you met on Tinder, a guy with a picture of Jesus on a cross, and you went for a long drive at night alone with him?”

She laughs.

“Yeah.”

“You must have immense faith in humanity.”

“Well,” she says. “I forgot to mention that I had turned down four dates with him. But it turned out that he’s a really nice guy, and he proposed to me some time back.” She raises her finger. There is a glittering ring.

“You are getting married.”

“I didn’t think I wanted to, but he is really nice and he’s the only person who has never given up on me. He’s so patient with me. So, this is a promise, engagement ring. He says he will buy me a proper ring.”

“Looking back and knowing what you know now, what would you tell your 19-year old self?”

“I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”

“Most of your problems come from your childhood, from your mom and dad. Do you think you have to resolve this to move forward?” I ask.

“A few months ago, my dad told me he loves me,” she says. “I’d gone home to visit them and we were having dinner and he just told me, ‘I love you very much.’ He said it like ten times. I almost broke down and cried in front of him but I ran to my room – yes, I still have a room at home, it’s more like a store now – and I cried. I got on my knees and thanked God. That was a very healing moment. My mom always reminds me now that she loves me. She calls me daily just to find out how I’m doing. She is no longer judgy. She is really psyched about me settling down. I can say honestly that my relationship with God has significantly improved because of my folks.”

“Have you told your fiancé about your wild days?”

“Are you serious?” she asks, laughing. “I told him about two guys and going by his reaction I don’t think I want to find out his reaction if I told all. I mean, would you want to know?”

“No,” I say. “Look, I hope you have a fulfilling marriage.”

“Thanks.”

“You see this outer shell, this is my body,” she explains. “But I always felt like I was trapped in this body that I was told wasn’t good enough, a body that I didn’t like. The real me was inside this body, this one right here.” She points at the smaller tooth in the big tooth. The picture, to be honest, looks like a big tooth who walked around, met a small tooth and lured it with sweets and then ate it. But if she insists that’s her, who are we to go against the artist?

“I know this sounds like something a mzungu would say,” she continues. “But I really felt like if I removed my body, if I came out of my body, this outer body that nobody liked, I would release the inner me who everybody would then like. I really admired a girl in my high school called Jean. I wanted to be like her. She was bold and she never took any nonsense from anybody. She didn’t care if you liked her or not. That’s who I felt I was inside. Outside I was a doormat, someone who couldn’t defend herself from the school bullies, from my parents and from society. People just walked all over me. Of course I tried being like Jean by not giving a shit and that was a problem for people and when I gave a shit that was also a problem.”

Suffice it to say she didn’t score enough points to join the university and she had big fights with her parents who were, again, disappointed in her.

“My mom had a way of loving you and hating you at the same time and it was very confusing,” she says. “She also seemed to want me to be like my sister. She told me that with a C-plain I would only sell tomatoes for a living and I believed everything she told me. I didn’t grow up being affirmed by anyone. I grew up being told negative things and when that comes from your mother and father, you believe it.”

She joined a private university and there she met Johnny. I don’t want you to raise your hopes and think that finally Johnny is the one who will rescue her. Johnny was an asshole. But a handsome and charming asshole. He was bronzed and broad shouldered and when he walked his feet barely touched the ground, like Ekwueme, son of Adaku and Wigwe in The Concubine. Girls kissed his ring in uni. He would swagger around campus beating girls off him with a wooden girl-swatter. He had the eyes of the most gorgeous girls, taking his pick from that sorority like an entitled emperor. Johnny, a trapper like Ekwueme, finally ensnares our protagonist into his web. She is confused. Her? Johnny? What did he see in her?

He saw her hips and ample bottom. He saw everything her mother had convinced her was big and bad and fat and he told her that she was fresh, that she could “gerrit”. He saw her physical beauty, because she is beautiful, and that took her aback because nobody had ever thought of her as beautiful and here was Johnny with his full Maxwell lips, blowing her kisses and making her giggle. For the first time she was taken on a proper date by a man, Johnny himself, the son of Adaku and Wigwe, to eat fries and chicken and drink soda at KFC because KFC at that time was all the rage and guys were actually lining up for it like it was manna. She fell for him then Johnny tapped it, as the university students say and if you are reading this from June of 1985, “tap it” is not a Morse code, it’s to have “sexual intercourse” with a woman. They were barely an item before Johnny said, “This isn’t working. I don’t want this anymore.”

The bottom fell off and she fell into a deep, dark pit.

“I had flirted with the idea that perhaps someone could love me when Johnny and I started dating but when he left me, I was sure that I didn’t deserve to be loved. That my parents had been right all along. What was I thinking, that I deserved love? My self hatred deepened to another level.”

For over a month she was dazed, walking barefoot on the sharp shards of her broken heart. She felt like she was bleeding on the inside. The pain in her heart was physical. She thought of suicide a few times. She wouldn’t eat or sleep. She would stay awake the whole night, staring at a lit candle burn out till darkness engulfed the whole room. “I still stare at burning candles. It’s my therapy.”

Meanwhile Johnny went about living his life as usual, a new bird hanging on his arm. She would see him in the cafeteria, making a knot of girls crumble in giggles. Or walking across the lawn, carrying his books in one hand, the sun in his face, a girl on the other hand. Good old Johnny going about his life without a f*ckn bruise. She looked at him and thought, how can this bastard move on like nothing happened, like a big love train just didn’t get off the rails here? How can he even breathe in the wreckage of my heart?

“This is when I made a decision in my life. That I would never have sex because of love. Or love because of sex. I’d never show my heart. That I’d operate like a man.”

“And just like that my whoring days started.”

And they continued right after university; she felled men like logs and left them lying there to rot in the soil. If you dared show or told her that you liked her, she would cut you loose. She also started drinking at some point, drinking heavily, and since she’s a lightweight, her drinking was three guaranas, maybe some vodkas, always in her house and only over the weekend.

“I didn’t know it then, but I was escaping,” she says. “I hated myself. I saw girls my age date decent guys while I was just jumping from one guy to the next. I was addicted to sex the way some people are addicted to alcohol or gambling. I wanted sex to numb the pain. A guy saying no was a challenge. It was easier to get naked for a guy than fall in love. Love became a metaphor, a fairy tale for other people. But with sex also came lunatics. I have seen all types of psychotic men in this town.”

She sips her coffee and collects her thoughts.

“Biko, I was dying inside and having sex and drinking was my way of trying to find solutions. I even tried counselling. It didn’t work. I was getting sicker and sicker. I would pray to God to help me get through the day without thinking about sex. At some point I tried to stab myself in the stomach with a knife to end it all. I held the knife to my stomach and started crying because I was weak and too cowardly. I remember going to see a pastor for counselling and he told me that I was just a horny girl and that my parents thought I was a loser. Can you believe it?” She laughs dryly. “In some ways I thought that if this pastor can say such things to me, then he also must be right. I was a sexual misfit.”

“So the biggest problem was not alcohol but sex?” I ask.

“Yeah. There were days I would be in the office and I would start trembling from being horny. I would be at my desk at 11am and my whole body would start shaking and I’d be so horny I’d not be able to think or do anything. I’d close my thighs tight and control my breathing. I’d walk around to let it pass and if it didn’t I’d start chatting up one of the men I was shagging and arrange for a meet up.”

“What if he was said he was busy?” I ask. (Like he has to take his cat to the cat dentist.)

“Then I’d hit up the next guy. I had guys lined up; if one said no, I’d holler at the next one. If he said he’s out of town, I’d go for guy C and D and so on,” she says. “I was having gruesome sex by this point, I liked to be shagged hard, to be roughed up, to be choked and my hair pulled against my scalp. Gruesome sex isn’t sex that you have to fulfill you. It’s empty. It’s the kind that ends up hurting you at the end of it. You end up not feeling good. I was punishing myself for being the way I was. I wanted to feel the pain for being who I was. At some point sex stopped having any effect on me. I tried to cover my pain, hatred, worthlessness and rejection with nice clothes and perfume but these things couldn’t fix me.”

It was like taking soda water.

“What’s your body count?” I ask her.

“I can’t tell you.” She sighs and looks away for the first time.

“Why not?”

Pause.

“Because I’m ashamed,” she says in a small voice.

She says it in a way that makes me want to hold her hand and tell her it doesn’t define her. She says it in a way that makes her vulnerable and little again, like that lonely, friendless girl in the school yard that nobody wanted to talk to. Those words, “because I’m ashamed,” make her brittle and innocent and it turns her heart into a small baby dove that hasn’t learnt about gravity.

On her 27th birthday she and a bunch of her drinking friends went to Westlands to celebrate. She promised herself that she wasn’t going to step into 28years living that life, it had aged her from the inside out. It was like she was carrying stones in her bones. She was going to have the last drink, the last sex.

She got a good lady pastor who was also a therapist. “She advised me to do an Esther’s fast, which is three days of fasting no water or food.” So she took some leave days and stayed in the house in her deera, curtains drawn, everything that emits sound switched off, just fasting and praying. “I prayed for God to take away my sexual urge. Sex was destroying me. It was a tool I was using to hurt myself.”

Somehow after the fast and prayers her urges reduced considerably. She stopped drinking. She deleted all the numbers she had of men she would sleep with. She lost almost all her friends who got swept away in this wave of change. She also lost her job and moved back home. The trembling stopped. She “backslid” twice, yes, but it wasn’t the same as before her fast. She found Jesus, afresh, got saved.

“It isn’t easy. I was in therapy every week with my pastor. I had to confront shit I’d avoided. It came to the surface. Lemme tell you when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it. Though I was going through a hard time, I found love in Christ. My parents attitude towards me has changed. They seem more appreciative and accommodating of me.”

We wait as the waitress clears the table.

“I have been going through a hard year and a half,” she continues. “Financially I wasn’t doing well but spiritually I was growing daily. My ability to overcome temptations was growing stronger. I began to believe in God and eventually I began to believe in myself. He fixed my esteem.”

To meet new people she joined Tinder one day in a moment of boredom. One day she matched with a guy whose profile picture was of Jesus on a cross. They started chatting. She liked his commitment to his faith. He also said he was abstaining. He asked her out four times before she agreed. “On our first date he came and picked me up and we went for a long drive around the southern bypass at night.”

“Wait. So you got into a car with a guy you met on Tinder, a guy with a picture of Jesus on a cross, and you went for a long drive at night alone with him?”

She laughs.

“Yeah.”

“You must have immense faith in humanity.”

“Well,” she says. “I forgot to mention that I had turned down four dates with him. But it turned out that he’s a really nice guy, and he proposed to me some time back.” She raises her finger. There is a glittering ring.

“You are getting married.”

“I didn’t think I wanted to, but he is really nice and he’s the only person who has never given up on me. He’s so patient with me. So, this is a promise, engagement ring. He says he will buy me a proper ring.”

“Looking back and knowing what you know now, what would you tell your 19-year old self?”

“I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”

“Most of your problems come from your childhood, from your mom and dad. Do you think you have to resolve this to move forward?” I ask.

“A few months ago, my dad told me he loves me,” she says. “I’d gone home to visit them and we were having dinner and he just told me, ‘I love you very much.’ He said it like ten times. I almost broke down and cried in front of him but I ran to my room – yes, I still have a room at home, it’s more like a store now – and I cried. I got on my knees and thanked God. That was a very healing moment. My mom always reminds me now that she loves me. She calls me daily just to find out how I’m doing. She is no longer judgy. She is really psyched about me settling down. I can say honestly that my relationship with God has significantly improved because of my folks.”

“Have you told your fiancé about your wild days?”

“Are you serious?” she asks, laughing. “I told him about two guys and going by his reaction I don’t think I want to find out his reaction if I told all. I mean, would you want to know?”

“No,” I say. “Look, I hope you have a fulfilling marriage.”

“Thanks.”

Discover more from Bikozulu

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pap

Kibet is that you?

Yetz! Asante Biko.

I’ve been waiting for a new e-mail notification all morning..Finally.!!

Ata sijaisoma bado.

But thanks for the new post!

Finally.

Awwwww…such a nice ending

Jesus really does wonders, eh?

Congratulations to her. Hope she has a blessed life and marriage.

Absolutely, this comment has made me remember Munishi,

Yesu ni mambo yote ndani ya yote, ukimpata yeye umepata vyote.

I wish her well.

My Take home….. Prayer works…

A friend of mine always says, “Where there is a (wo)man to pray, there is a God to answer.”

This right here is proof that God hears and He delivers.. All we need to do is ask 🙂

There is hope

I know I shouldn’t be laughing but come on…

But there are some stuff in here just too funny to pass on (…for me because Meru words sound like termites crawling down your nose making you want to sneeze but you can’t because you have food in your mouth…)

May she completely conquer her demons someday, and marry ‘her’ Jesus wholesomely

Finally we have a story yaaay! And it’s not just a story; it’s a touching story. Really deep.

I hope that everyone reading this who is a parent or is an aspiring parent sees just how much how we choose to parent our kids affects them. I feel like if her mom had been more kind and sensitive and affirming, things would have been different.

I like that she says that rough sex just hurts you and leaves you empty

My favourite part is that despite everything, she has found love.

Love is so beautiful.

Like Biko, I hope you have a fulfilling marriage and thank you so much for being brave and sharing your life with us

PS: Your body count definitely does not define you. I hope one day you’ll not be ashamed about it because you overcame those days.

Parents – Affirm your kids, love them equally and be there for them. In the words of Maghoha, “Stop putting stupid pressure on them”.

Pastors – I dunno man. Get some counseling training maybe? Read a bit on the psychology of recovery or stuff that won’t have you dismissing hemorrhaging people with textbook answers. (I have heard enough stories of clergymen that played central roles in damning broken people’s lives. People clutching on them as the last straw)

I was afraid of how this story was about to end. What a turnaround. A perfect analogy of calm after storms. In your words Biko, I too hope she has a fullfilling marriage.

You’ve summed this up so beautifully, taken every aspect into consideration. Well inI!!!!

How do I like this comment more than once! Very well put Peter Wesh.

my dad beat my mum ….three times …when i was transitioning from high school to uni. so one time he beat her and i ran to church to tell him how my mum needed saving , do you know this guy said ”Mambo ya familia htuingilii ”.

he is now the priest for our lady of the rosary, ridge ways . short priest who wears spectacles.

i think thats one of the reasons i find the catholic church unrelatable to. im the only protestant in my family,

i can relate with this chick. only mine was more vicious because my dad loved me so much my mum in her insecurities said i was sleeping with my dad and made a point of telling my dads sister. in between that vicious attack and other things like being wide hipped when my mum is petite , my brother is hazel eyed, body shaming was a family joke for them but mehn the relationships i got into that left me more broken.

Here is to a celebration of becoming better and belonging to a church that accepts me and loved me. here to ‘Alight in the City ‘ . and here is to every girl whose pain would ease if i told my story but i cant because i come from a family whose image is everything.

oh baby..i can only imagine the pain you went through especially knowing whatever was being said was not true.Parents really need to understand that its a vocation from God.I hope you heal if you havent yet and may you find peace.xx

..,…I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”…..

Nice read Biko

well… this was truly worth the 2-week long wait!! I’ve been taken through so many emotions in less than 30 minutes… but I am glad in the end she acknowledged God’s role in changing her whole life and touching every single broken part of her… great job, Chocolate Man!!

I’m glad she found some help.

And for sure,when we turn to God and we let him take over,he does wonders.

“I’d tell her it’s going to get better,” she says. “Don’t get lost in the shit that’s happening momentarily. Don’t write yourself off, keep praying and trusting God, He hasn’t summarised you. It will be better. Most of all get the right help.”

My take home for today!

Wow, this is a good one. I love good endings.

It always has to be a Johnyy.

If you deny a girl child love when she is young she ends up losing her self in alcohol and men trying to find love that she lacked……

I am confident it’s only Gods Grace that can fill that void and make one turn over a new leaf

Thanks for sharing this biko

Yaani Biko, thank you for this one.

I’m hardly one to comment on these pieces. But this is such a deep piece.

No story is too difficult to turn around. I like the honesty she has with herself foremost, and the courage to name her demons and what she struggles with.

I really do believe God is the only person who can fill any void we have- things may give us momentary satisfaction but they can never quite fill that void. And a relationship with God is something so personal, and beautiful.

Really happy for this lady, and that she found her man after dealing with her personal demons. I do hope one day she can find a way to be truly open with her fiance about her past.. because that’s what it is, a past.

Like take his cat to the cat’s dentist…

Really Biko???

Thanks though, this has been a very splendid read…it’s bustling with hope…it renews a new hope in the good book.

A reminder that even when we have given up on ourselves, God is there waiting for us and His grace is sufficient in our lives.

Congratulations to her.

The power of parents…may we never take this lightly.

Pretty sure it’s gatinkú

Most definitely it is

Ii ma i gatinkú. The pronunciation of the word is way different. The two can not be confused. Granted we have words where we add a few Ns and Ms but this is not one of them.

I’ve learnt words of affirmation are essential in any relationship; from child-parent , boy-girl and wife-husband. Only use these words when you mean it.

Only God can heal our brokenness , i pray it works out for her. as for parents stop having favorites, love your kids equally

“when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it.”

I’m not a believer but she makes me wanna believe in God. May her marriage be successful.

We are all believers, we just believe in different things (and some are more accurate in their beliefs than others. We are all believers.

Lemme tell you when you let God take over, He touches everything. He gives you the grace to handle it. Though I was going through a hard time, I found love in Christ. Favourite line

Tough one. I can relate to loving but not liking your parents. Can also relate to parents having favorite kids. Its a very painful thing to come to terms with. I remember feeling unloved and wishing id never been born. Parents can truly ruin ones self esteem, its sad.

I like her drawing. It does look like a molar though lol. Still cute. I cant draw so.

I wish her all the best.

I can relate I also grew up in such environment. My mother is light skinned contrary to me. I am somehow chocolate. She would constantly call me names, call me dirty that I should scrub my face. I remember the many creams she bought for me at a tender age of ten. It is painful to remember. I am 26 now, married with a son but still whenever I visit her there’s always something wrong with my face. Thank God my husband reminds me I am beautiful.

It is a long story with bad memories. My brother was always favored over me.

You are beautiful and am glad you found someone who thinks so too. You do not have to visit your mum. Be happy dear

Hey. This is deep

It’s left me conflicted too, abt the ‘proper’ way to live, is there ever one?

Suffice it thus, the end justifies the means

Ngatinku, move on

And find more happier days. You deserve it

Anyone else having trust issues with Biko’s posts recently? I had to scroll through first to confirm that its a full post.

What happened to the Uber chap?

Sounds like you read Philip Etemesi’s novel ‘The Fornicator’ coz this story is very similar to the one in his book. Are you sure this is a true story or it was inspired by that book?

well, you know let me give you a shocker some people lives sounds like a story from the novel. Stuff like ths happen

You may not realize it or have intended it but when you question a content creators authenticity, you hurt them very in a very personal way. It is like telling them they are not good enough, they just copy other people’s ideas.

Millennial problems. Find one thing amiss from your childhood and use it as an excuse to be a rebel. Hehe. Seriously though, take a look at the people you know. There must be one with the perfect love of both parents and everything you think you missed. Now look again, is there a child of their’s acting up for something different?

Well, its always one thing or another. Don’t make your childhood your poison, folks!

Easier said than done

I dont think its fair to be judgemental towards someone when you have not walked in their shoes. Its important for people to heal what hurts them inorder to live healthy lives. And yes no ones life is perfect but imperfections are not the same and they dont affect people in the same measure.

I said what I said.

You can choose to focus on those imperfections to your own detriment.

From a point of no experience ,,everyone becomes judgemental.Sad

I know we add N’s and M’s unnecessarily, but it is GATINKU

Nice read there Biko….

My take-home: Parent’s have a big role to play in their child’s life….affirm and love all your children unconditionally, coz that plays a big role in their future (self-esteem and confidence). As parents, we should go beyond just providing for the family…..

I am still stuck at “blew our tea before sipping it, like Kales in Bomet”…..yeah we do that ‘No human is limited Inyeos 🙂

no human is limited indeeed.. inyeos .. hahahaha i am off to CHEKENYAE (JKIA)

Parents have a big role to play in the future of their children. let us affirm them more and love them equally. abroken child is a broken society.